VEDAANTA

DESIKA

PROF. K. R. RAJAGOPALAN

There have been many centenary celebrations in the recent past;

but one which has, perhaps, not been so widely known is the sapta-centenary

of Vedanta Desika which was celebrated in 1968. Even during

1968, college students did not know who Desika was–as

brought out in a Quiz programme that year. The purpose of this short article is

to acquaint the readers with this illustrious son of Tamil Nadu

who lived seven hundred years ago.

The town of

All groups of Hindus derive their authority from the Vedas, so too

Sreevaishnava Siddhaanta

(as it is locally called in Tamil Nadu) or Visishtaadwaita Siddhaanta.

The Aalwaars of this land gave the

quintessence of the Vedic Dharma in Tamil verses called Naalaayira

Prabandham. These ideas were codified into a

philosophy and a way of life by Aachaarya Raamaanuja who lived in the 11th-12th centuries. This

scheme of rivivalism got an impetus from the revered Vedaanta Desika who systematised the daily life of a Sreevaishnava;

elucidated many of the earlier writings by his commentaries; served as a

rallying point in times of theological stress and strain; and gave the

followers of Sree Raamaanuja

his immortal grantha Rakasya-traya-saara,

in which the concept of prapatti or

surrender is fully explained. His influence has been so profound that he is

referred to one of the trio–Aalwaars, Sree Raamaanuja and Desika.

His Life

Vedaanta Desika

was the only son of a very pious and devout couple in the picturesque village

called Tooppul near Kaancheepuram.

His father Anantasoori named him Venkatanaatha–after

the Lord of the Tirumalai Hills with whose

graciousness the child was supposed to have been born. His mother was Totaarambaa. Venkatanaatha had

his Upanayanam at an early age and

started his education under his maternal uncle Appullaar

or Aatreya Raamaanuja.

Before he was twenty, he learnt all that was possible and became quite

proficient in expounding the Sree Bhaashya–the

magnum Opus of Aachaarya Raamaanuja. He married Tirumangaiyar

perhaps in 1289 and lived the life of a Grihastha

in the traditional manner. This couple had an only son– Varadaacharya

who was born when Venkatanaatha was 46 years old. He

lived mostly in Kaanchipuram, Sreerangam,

Tiruvaheendrapuram (near Cuddalore ) – going from one

place to another in response to the invitations of the residents either to give

learned discourses or to conduct dialogues with people professing other faiths.

When Mohammedans invaded Sreerangam and desecrated

the temple there, Venkatanaatha went to Satyamangalam (in the

Like many of the other great personages in history, he too is

credited with having worked a number of miracles–but his greatness does not rest

on them. Quite a large number of stories and anecdotes have been wound round

his name and works; but we would not go into them here.

His Works

The mere cataloguing of his works

would be an exercise in itself–his output is so

large and varied! He has compositions agalore in

Samskrit, Praakrit and Tan1il–besides ManiPravaalam,

an admixture of Samskrit and Tamil. His Tamil works are

affectionately referred to as Desika Prabandham (as a sequel to the Naalaayira

Prabandham of the Aalwaars).

He is reputed to have composed 119 works all of which are not now

available. They may be classified into the following six headings–manuals of Sree Vaishnava religion and esoterism; theses on Sree Vaishnava theology and ritualism; devotional and didactic

poetry; literary works; original philosophical treatises; and commentaries.

For popularising the ideas and ideals of

Sree Vaishnavism and

spreading the religion and philosophy of the Aalwaars

and Aachaaryas, Venkatanaatha

wrote a number of manuals of which the following may be mentioned–Nyaasa Dasakam, Vaishnava Dinacharyaa, Vairaagya Panchakam, Sampradaaya Parisuddhi and Paramapada

Sopaanam–in sanskrit,

Tamil and Manipravaalam. Out of these, the first

mentioned small work of ten stanzas explains in simple language the concept of Saranaagati or complete surrender of oneself

to the Lord. A free translation of one them is: “I, whom am bereft of anything

tangible, with no other refuge, in full faith and confidence that You will protect me, pray to You, the giver of all, to

accept my bondage to You.”1 This exemplifies all the five Angas of Saranaagati

or Prapatti. The Vairaagya Panchakam contains

the following famous words: “I do not have any legacy left by my forefathers;

neither have I earned anything (in my life); at the top of the Hastigiri (Kaanchi temple) is my

family treasure.”

The characteristic features of Sree Vaishnavism are sought to be explained in the following

works of his–Nikshepa

Raksha, Rahasyatraya-saara.

The latter is his magnum opus, written in a highly Samskritised Tamil with a number of Samskrit slokas interspersed

and explains the full significance of Visishtaadwaitic

thought, philosophy and religion. This work is held in very high esteem and is

studied only with the help of one’s Aachaarya.

Rahasya-traya-saaram is an

exposition of the three Rahasyas which form the

essence of teaching to the Sishya from the Guru. They are: (i)

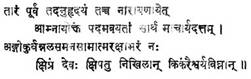

the Moolamantra viz., ![]() (Sreemate Naaraayanaaya Namaha); (2) the Dwayamantra viz.,

(Sreemate Naaraayanaaya Namaha); (2) the Dwayamantra viz., ![]()

![]() (Sreeman Naaraayana Charanow Saranam Prapadye Sreemate Kaaraayanaaya Namaha) and (3) The Charama sloka viz.,

(Sreeman Naaraayana Charanow Saranam Prapadye Sreemate Kaaraayanaaya Namaha) and (3) The Charama sloka viz.,

![]()

Sarva Dharmaan

Parityajya Maamekam Saranam Vraja

Aham twaa Sarvapaapebhyo

Mokshayishyaami Maasuchaha.

These are to be learnt direct from the Guru alone with his

blessings and hence the Guru. nay, the Guruparampara itself, is held in very high esteem in Visishtaadwaitic thought and religion.

Vedaanta Desika

has expounded and explained the concept of Saranaagati

(Complete surrender to the Lord) in the above work which is in a highly Samskritised Tamil interspersed with Samskrit stanzas. A

few are given below:

[Moolamantraadhikaaraha-stanza

I]

Taaram Poorvam

Tadanuhrudayam Taccha Naaraayanaayet

Aamnaayoktam Padamavayataam Saarthamaachaarya Dattam

Angeekurvan Alasamanasaamaatmarakshaabharam

Kshipram Devaha

Kshipatu Nikhilaan Kinkaraiswarya Vighnaan

The Moolamantra is praised as follows–(It) has Pranava

(Om) in the beginning, then Namaha

in the middle and Naaraayanaaya who is revered in

the Vedas at the end; may the Lord accept the burden of us who have learnt the

meaning of this Mantra through the (kindness of) Guru and may He remove the

impediments in our attaining the wealth of service to the Lord.

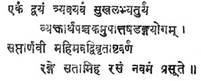

The second of the Rahasyaas, the Dwayamantra is spoken of the next stanza viz.,

(Dwayamantraadhikaaraka - last stanza)

Ekam Dwayam

Tryavayavam Sukhalabhyaturyam

Vyaktaartha Panchakamupaatta

Shadangayogam

Saptaarnavee mahimavadvivritaashta Varnam

Range Sataamiha Rasam Navamam Prasoote.

A free translation would be–“This has only one sentence but is of

called Dwayam or two-fold; has three sub-sentences; can give you easily

the fourth sukha (Dharma, Artha,

Kaama, Moksha); explain.

the five-fold meanings; gives one of the six ways of the Prapattiyoga; is as famous as the seven oceans;

expounds the Ashtaaksharam or the eight-syllabled Mantra; and gives the ninth Rasa (viz.

Saanti) to those in this world.

The stringing together of the numbers from one to nine in this sloka is to be specially noticed.

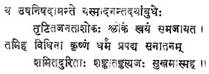

The next quotation is from the Charamaslokaadhikaaraha,

to explain the excellence of that stanza:

Sree Krishna is near the Upanishads, and

is the embodiment of the vast world of kindness; from Him the Charamasloka came out by itself and it removed the sorrows

of the common men (Janata) of this world; we, due to

our good luck, have got Krishna as our saviour and

(so) we shall have no doubts or fears regarding our salvation; but, having been

freed of our sins, we shall live (always) in happiness.

His poetic exuberance found expression in a series of verses

composed in praise of the Lord in His manifestations in various forms and in

various places. To mention only a few: We have the Kaamaasikaastakam

on the Nrisimha shrine in Kaanchi;

the Hayagreevastotra on the diety at Tiruvaheendrapuram ; Bhagavaddhyaanasopaanam on Sreerangam; Varadaraaja

Panchaasat, a string of fifty verses on Varadaraaja of Kaanchi; Dayaasatakam, a garland of hundred verses on Venkatanaatha, the Lord of the Seven Hills. His imagery is

indeed very much different from that of many others, who also have sung similar

poems. Venkatanaatha has composed Dasaavataara

Stotram on the die ties of the unique temple in Sreerangam in which the ten Avataaraas

of Vishnu are depicted as Moolavigrahaas. The

stanza in which he combines all the ten Avataaraas is

indeed representative of the individualistic way of presentation:

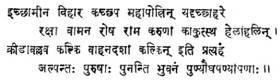

God assumed the Matsya form

due to the desire (![]() )

of enjoying a sojourn in the waves; the Kurma

fonn for playing (

)

of enjoying a sojourn in the waves; the Kurma

fonn for playing ( ![]() ); the Varaaha

form is noted for its size, as the entire earth had to be lifted out of the

ocean by the Varaaha; God took upon the Nrisimha form “just like that”–had not made preparations before

evidently. The Vaamana was for

protecting the pious; Parasuraama was

noted for his quick anger; Daasarathi Raama for his Karuna

naturally and Balaraama for his plough;

); the Varaaha

form is noted for its size, as the entire earth had to be lifted out of the

ocean by the Varaaha; God took upon the Nrisimha form “just like that”–had not made preparations before

evidently. The Vaamana was for

protecting the pious; Parasuraama was

noted for his quick anger; Daasarathi Raama for his Karuna

naturally and Balaraama for his plough;

Many of these stotras are being recited

everyday in many homes: these form the introduction of the children to Vedaanta Desika. His Garudadandakam in Dandaka

meter, a rythmic prose piece and Raghuveera Gadyam in

poetic prose are also famous as pieces to be set for recitation; he has an Achyuthasatakam in Praakrit

too; containing 101 Gathas.

There are other longer works of his also Paadukaasahasram

is a long poem of 1008 verses traditionally said to have been composed

within three hours of the night.

These verses sing the glory of the Paadukaa

of Sri Ranganaatha [who, according to Desika, assumed the ten Avataaraas]. It has been said that this

poem “is a study into the Raamaayana of

Vaalmeeki bringing out all its niceties as an epic

poem of love and devotion.”

Yaadavaabhyudaya is a Mahaakaavya

on the lines of Raghuvamsam containing

24 cantos describing the Yadu race,

On the model of Meghasandesa, Desika has a Hamsasandesha

containing 110 verses in two

parts. The first thereof describes the places over which the swan is to go to

convey the message of Rama to Sita who is held in captivity in Lanka. The

second part deals with the intense love of Rama to Sita–bringing out the

![]()

Soul’s

outpourings to the Divine from whom it has been separated and is pining to be

reunited.

In addition to the above, Vedaanta Desika has written original philosophical treatises and

commentaries also. Nyaayaparisuddhi, Tatwa-muktaakalaapa (which is quoted by Maadhavachaarya Vidyaaranya in

13th century) and Adhikaranasaaraavali an

exposition of Brahmasutra are some of

them. Of no less importance are his commentaries –Tatwateeka, an

exposition of the Sree Bhaashya;

a supercommentary called Taatparya

Chandrika on the Geetaa

Bhaashya of Sree Raamaanujaachaarya; one in Samskrit and another in Tamil,

on the Geethaartha Sangraha

of Yaamunaachaarya and on the three Gadyas of Sree Raamaanuja.

He was respected and revered even during his time; later too, other

poets and scholars have referred to him in very appreciative terms. Venkataadhwarin a writer of 17th century states in his Viswagunaardarsachampu

that Kaanchi derives its glory due to its being

the birth-place of Vedaanta Desika,

who was an ideal man of all times. He was conferred such honorifics as sarvatantraswatantra (master of all arts). Kavitaarkikasimha (Lion of logic), Vedantaachaarya, Vedaanta

Desika. Even as early as 1350, he was considered

good enough to be quoted upon in Maadhavaachaarya’s Sarvadarsanasangraha, as an authority for Raamaanuja’s philosophy. Doddaacharya in 16th century has written a

biography of Desika called Vaibkavaprakasika.

Pillai Lokaacharya, a

contemporary of Desika, was instrumental in saving

the Utsava idol of Sree Ranganatha of Sreerangam from

Muslim vandals; he is credited with a benedictory verse on Desika.

Today, Desika is almost deified by his followers–his name is invoked before doing any important religious

festival in many families. Perhaps this has not been without its bad effects–his exemplary life and austere

habits have been almost forgotten and only

pooja to his idol is being performed!

Venkatanaatha performed the duties of a Sreevaishnava with great devotion; he discharged his

obligations including that of teaching his Son Varadaachaarya.

He lived up to his teachings–a

saying which could be mentioned with regard to few people.

Such an illustrious personage is likely to make an appearance once

in several centuries only. “He was an institution in himself and his philosophy

a mission.”

1

![]()