Some Thoughts on Similes

BY

RAJASEVAPRASAKTA N. RAMA RAO

“Simile

(Latin neutral of similis, like) is a

comparison of one thing with another, especially as an ornament in poetry or

rhetoric.” The comparison should be both true and beautiful, and what is more,

the juxtaposition must result in a revealing flash that illuminates both the

things compared. The statement of a mere resemblance, without truth, or beauty,

or illumination, is a banality. As Johnson said, a simile to be perfect must

both illustrate and ennoble the subject, and Addison declared that one of the

secrets of Milton’s sublimity was that he “never quits his simile till it rises

to some very great idea.”

Most

people, I believe, have moods in which they love to summon up remembrance of

things which have been a joy to them. Words and thoughts which have comforted

me in my journey are often with me as I spend a solitary evening in my

arm-chair, or go out for an early walk to take the morning air and revel in the

freedom of sun-lit spaces. At such times, similes that I have loved come back

to me, with a fresh wonder that is almost awe.

A

simile derives its beauty and illumination from the oneness of the Universe,

and is not only poetry but philosophy. It is a flash of revelation, and the

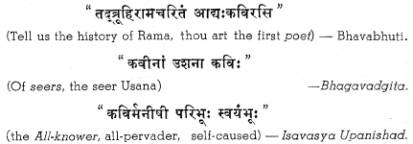

poet who sees and utters it, is a seer. It is, therefore, not by chance, nor

yet owing to penury of language that the Sanskrit word for poet means also seer

and the All-knower. As, witness:

A

simile is the expression of that essential unity of all things, which flashes

upon the inward eye which is the bliss of solitude, and which can get a

glimpse, be it never so evanescent, of reality.

How

beautiful, and yet how simple-and, once seen, how self-evident-are such similes

as:

“I

wandered lonely as a cloud.” –Wordsworth.

“Perhaps

losing hold of both (this world and the next) he is lost like a torn cloud in

the vastness of the Eternal” –Bhagavadgita.

Here

is the yearning of a life left from its setting, and all too aware of its

desolation. This sadness–all mutt have felt it at one time or another in

varying degrees of acuteness–what a background it is for the joy of fulfillment

when the lonely poet found himself caught up in the (gaiety of a jocund

company, when all at once he came upon a crowd of golden daffodils fluttering

and dancing in the breeze, tossing their heads in sprightly dance, outdoing in

glee the sparkling waves that danced beside them; and-in the other case-when

the soul. drifting like a lost wisp of vapour in space beheld the truth, and in

the rapture of realisation exclaimed:

“All

before is Brahma and Immortality–all behind–all above–all below–verily, All is Brahma.”

–(Mundaka Upanishad)

The

earliest literature, as we see it in the Vedic hymns, is figurative;

impressionist, as the earliest script is pictorial -and for the same reason.

The mind observes, but it has not come to analyse and make abstractions. Things

are still things, and have not become symbols. The most prevalent figure is

personification, and the most frequent approach, the apostrophe, There are

sometimes similes and metaphors (a metaphor is just an abbreviated simile) of

surpassing beauty, incandescent from the seers mind.

The

following extracts from the Hymn to Night in the Rigveda is an example:

Night

approaching looketh forth in many places with her eyes. She hath put on all her

glories.

The

immortal Goddess has pervaded the wide space, the depths and the heights.

So

hast thou come to us today and at thy coming, we do go home, as birds to their

nest on the tree.

Home

have gone the villagers, home all creatures, even the greedy hawks.

Ward

off the she-wolf and the wolf, ward off the thief, O Night; be thou happy for

us to pass.

The

Darkness, thick, painting black, palpable, has enveloped me; O Dawn, clear it

off like debts.

(R. V. X-127)

The

words of solemn Farewell to loved ones Hymn are strong with courage and hope:

“Go

forth, go forth by those ancient paths your fathers trod.”

The

Upanishads mark a further step in the development of the simile. The

resemblances are not only observed, but pursued in thought. The series of

beautiful similes in the Chhandogya whereby

the sage Aruni illustrates to Svetaketu the identity of the individual soul

with the Eternal–that thou art–are

perfect of their kind, and would lose by an abridged quotation. The invocation

of the dying sage in the Isavasya to

the Sun who “as with a golden cover hideth the face of Truth” beseeching him to

gather up and withdraw his dazzling rays, so that the sage’s dying eyes might

look unafraid on the absolute Truth, is difficult to match in literature. But

perhaps the simile most impressive of all in its sublimity is the following

from the Mundaka:

“Seize

then the mighty bow, the Upanishad; place on the string the arrow of thy Soul

sharpened by constant meditation, make the Brahman thy mark, and courageously

shoot thyself forth to reach thy mark.”

It

is no matter, for wonder that Shankaracharya’s mind, saturated as it was with

the Upanishads, imaged itself forth in similes of a grandeur hardly inferior:

“The

Asvattha is the tree of life–the

manifest world of living beings, changing from moment to moment, and vanishing

like an illusion, or the waters of a mirage or a cloud-city............... It

bears the sweet flowers love and charity, self-sacrifice and renunciation. In

it are the nests of myriad life, tumultuous with the many-toned voices of

pleasure and pain, love and dancing and laughter, and groans, wringing of hands

and loud lamentation. It is cut down by the axe of detachment.”

The

classical period was rich in poets of whom any age or clime might be

proud–Kalidasa Bhavabhuti, Bharavi, Bana, Magha, and others illustrious in

Indian Literature. Kalidasa, prince of poets, was universally acknowledged the

unrivalled master of simile.

The

similes in Kalidasa are invariably examples, taken at random, will illustrate:

“Parvati

and Parameswara, the parents of the Universe, inseparable as the word and its

meaning”

–Raghuvamsa.

“Saddening

yet beautiful is this love-lorn maid drooping like the madhavi creeper whose leaves have been oppressed by the summer

wind.”

–Shakuntala.

This

puts one in mind of Tennyson’s

“My

passion, sweeping through me left me dry” –only, it is incomparably better

poetry.

Perhaps

the most perfect simile in literature is in the description of Queen

Sudakshina, the expectant mother of Raghu. No translation can do justice to the

original–and here (with many apologies) is the nearest I could come to it in

English:

Her

jewels laid aside, till but a few

Sparkled

upon her drooping slenderness,

Her

face, set in her tresses, now the hue

Of

lodhra in its pallid tenderness,

Fair

as the fainting night at dawn of day

With

pale moon, in a thinly spangled sky

Was

the sweet queen, as glowing in her lay

The

rising sun of Manu’s lineage high.

The

best of translations are but shadows, and this is a poor one, containing at

least twice as many words as the original–words, too, which to the Sanskrit are as withered leaves to flowers bathed in

dew.

You

find in the original, set to the music of immortal verse, the pale moon of the

fading night, the hushed expectancy of a cold gray world yearning for sunrise,

on the one side; and on the other, the sweet young queen wan and faint with her

hero-burden, and the eager country waiting for the birth of a great king.

Only

a Shakespeare could render a Kalidasa adequately–but, then, a Shakespeare would

not need to render any body but himself to reach the very summit of human

language. The one simile that occurs to me as challenging a place with

Kalidasa’s is in Troilus and Cressida:

“We

two, that with so many thousand sighs

Did buy each other, must poorly sell

ourselves

With

the rude brevity and discharge of one.

Injurious

time, now with a robber’s haste

Crams

his rich thievery up, he knows not how;

As

many farewells as be stars In heaven,

With

distinct breath, and consigned kisses to them,

He

fumbles up into a loose adieu,

And

scants us with a single famished kiss,

Distasted

with the salt of broken tears”

I

wonder if the power of words could go any further -this is the very anguish of

a sudden parting such as presses the life from out young hearts,” darkens the

face of the sky, and makes a bleak promontory of the world. If Kalidasa’s

simile is the glory and travail of sunrise, Shakespeare’s is the agony of “a

huge eclipse of sun and moon.”

So

far I have spoken of similes on the large and elaborated scale. There is yet

another kind, small and dainty rather than grand, which is to the other as

jessamine to the lotus–and which is to be found in all true poetry, as for

example:

“With

thirsty eyes the queen drank her lord’s presence.” –Raghuvamsa.

“The

thirst that from the soul doth rise.” –Ben

Jonson.

“The

moon over the night her silver mantle threw.” –Milton

“Poor

withered leaf, where goest thou?”

“I

go where all things go

Where

goes the petal of the rose,

And

the leaf of the laurel” –Arnault.

Poetically,

the most beautiful use of such flowerets is their harmonious combination into a

colourful pattern of the poets fancy. Here is an exquisite example from Bhasa

(a description of winter):

“The

lord of the night is wan

like

a damsel parted from her beloved;

Feeble

now are the rays of the sun

like

the behests of fallen greatness;

Without,

the snow-laden wind is

cruel,

like the clasp of a pretended friend;

But

the fireside within, with its

smarting

smoke, is sweet like

the

young wife in her first love-quarrel.”

Here

are a number of images beautiful in themselves–the pale wintry moon, the wan

love-lorn maid waiting for her lover, the sun shorn of his erstwhile power, the

snow-laden winter-wind, sharp like benefits forgot, the young couple in their

first lovers’ difference, and the welcome warmth of the homely fire, with its

provocative tang of smoke.