Some Similes of Kalidasa *

BY P. MAHADEVAN

Although Kalidasa has been the touchstone of our

national literary taste for well nigh two thousand years, it cannot be said

that Indian scholarship has made any sustained attempt to consider his genius

against the background of a universal poetic tradition that would include along

with Valmiki, Homer, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare and Milton. The best work on

our national poet has been done by foreigners; but even they have not entirely

been free from more or less faint suggestions of patronage. It is, however, a

remarkable fact that his poetry has a power of suggestive anticipation of many

of the felicities which have subsequently found varied expression in later

poets of recognised universal appeal.

We of the present generation of English-educated

Indians have been speaking with amorphous enthusiasm of a renaissance of our

literatures, thanks to our contact with the West through its books. We have

played–some of us are still playing–the sedulous ape to our distant exemplars,

actuated by a mystic faith that thereby the rock would burst, and the waters of

inspiration gush forth in an unfailing stream. Our zeal as proselytes has been

unquestionable, but we have made no progress beyond the gates. For all

practical purposes, we have fallen between two stools–aliens at home and

ignored abroad; and that sterility is the badge of our tribe. A few of us have

achieved the ambiguous distinction of an exotic flowering; but the blossoms

have no fragrance, and their colours look blighted by a congenital anaemia. We

have imitators of the latest school of English poets, but not many to pay

homage to the greatness of Kalidasa. We have not even managed to give the world

one edition of his works in English which is at once scholarly, simple, elegant

and readable. Without some such renovation of our classics, I do not know how a

renaissance, in the accepted sense of the term, can be expected to be brought

about.

It is with a view to show that a study of our

ancient Indian classics in the modern setting is very much worth while that I

have ventured to draw attention to some of the many similarities in idea or

imagery between the poetry of Kalidasa, on the one hand, and the poetry of

English poets, on the other. I am too acutely conscious of my limitations to

attempt anything but an exploration of the outermost fringe of the subject. I

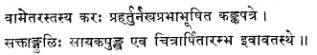

feel tempted to exclaim with the poet:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: I–2)

applying the mot not to the resplendent race of the Raghus, but

to the poet himself as one of the authentic children of the god of light, who

is elsewhere celebrated as the god of song also. But my excuse is that poets

form a world-brotherhood who recognise no frontiers. To love anyone of them is

to love them all. I see him, as it were, through a glass darkly; but it is my

hope that others better equipped than myself might do adequate justice to the

point of view which I commend to their acceptance. Like the merry Grecian

coaster, I shall skip from island to neighbouring island. The sedate scholar,

like the grave Tyrian trader, carrying his much more precious cargo, need not

avert his face from me, but even tolerate me as one of the light-hearted

mariners of the waves whose frail craft is unseaworthy, and who has no

intention of disputing with him the mastery of the ocean.

II

The antiquity of the simile may be said to be

co-eval with that of poetry itself. Indeed, when the first simile was thought

of, poetry may be said to have been born. Its function has ever been to

clarify, emphasise or embellish thought through speech. It is the spontaneous

expression of the wonder of the unfolding mind trying to be at home in the

world, to organise its impressions of it, and evolve out of them patterns of

feeling, thought or action. It is the parent of all figures of speech, all alankaras,

which are at the root of the basic distinction between prose and verse. The

metaphor implies it, hyperbole exaggerates it, fallacy transfers it, allusion

equates it, while suggestion, reminiscence, echo or flavour are like clouds of

glory trailing round it. Alliteration exploits it first through sound, and then

proceeds to sense through puns. The dispraise of puns in the English literary

tradition has always seemed to me a piece of critical obscurantism. It is, I

feel, an indirect confession of the difficulty of managing them. But the

greatest poets have always delighted in it; and our Dandin puts it in the

forefront of the qualities which distinguish Kalidasa’s poetry:

![]()

a judgement which, for its bland perspicacity, might have won Horsce’s

approval or roused Pope’s envy. Shakespeare reveled in it both in his gay and

grave moments, and remains without a fellow in English literature. Therefore,

to consider poetry abstracted from the simile is to attempt to think of vak

independently of the artha.

All similes can be considered under one of two

heads–the universal and the particular. The same symbols may have different

significations to different people, or the same ideas be conveyed by different

symbols at different times and places. The limiting factors are provided by the

accidents of race geography, history, flora and fauna. The apprehension of

beauty has ever been subjective, but must needs convey itself through objective

symbols. A given frame of mind or phase of thought colours what is seen so

variously as to give us all the rasas according to the context. The

scope of Kalidasa’s similes embraces the entire gamut of life and he plays

infinite variations on it. Nature and human nature, art and the inexhaustible

treasures of a mythology, which is still a reality deep down in the

consciousness of our race, invest his poetry with the light that never was on

sea or land.

It is worthy of note that one kind of simile, the

epic or Homeric, is conspicuous by its absence from Sanskrit poetry. Instead,

we have complete parallelisms which may be described as the logical

consummation of the epic simile. The charm of the latter arises, as we know,

from its naivete; but it is also an indication that the poet loses the thread

of his it narrative with the inconsequence of a child attempting to tell a

story. In Valmiki similes flash out in single words or brief phrases that

illumine without interrupting, the narrative. Complete parallelisms represent a

more conscious, or self-conscious, stage in which the poet stands out of his

theme, and distils the essence of it from all points of view. I shall not

presume to determine the rival claims of the two kinds of simile, but shall

content myself with the safe remark that much might be said on both sides.

III

Most of us are familiar with the famous description

of a cloud

that’s dragonish,

A vapour sometimes like a bear or lion,

Sometimes a tower’d citadel, a pendent rock.

A forked mountain or blue promontory.

(Antony and Cleopatra.)

–Impressive and realistic at the same time, and within the observation

of all of us. Shakespeare’s cloud is static, is really and objectively a cloud.

But Kalidasa sees in it the animated shapes of majestic elephants disporting

themselves in their forest homes on the slopes of mountains.

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–2)

The justice of the comparison cannot be fully appreciated by those who

have neither our mountains, nor our clouds nor our elephants. Mr. Eliot has

given us in his Prufrock a vigorous description of the antics of the

London fog by seeing in it the movements of a cat:

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the

window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the

window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from

chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

–as complete in its own way, and more meticulously minute as befits our

modern scientific temper! We are told that Mr. Eliot is a student of Sanskrit;

and it would be interesting to know if he was aware of Kalidasa’s simile when

he achieved the above tour de force.

Milton speaks of a ‘sable cloud that turns forth her

silver lining on the night.’ Kalidasa goes to the goldsmith for a similar

comparison:

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–37)

Keats speaks of the beadsman’s prayers going up ‘in

a frosted breath like incense.’ Rossetti speaks of hearing the tears that fell

from the eyes of the ‘blessed damozel.’ But I do not think there is in English

poetry such a bold conceit as Kalidasa’s

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–58)

Siva’s laughter congealed into the snowy peaks of

the Himalayas must be deemed sui generis.

Longfellow says:

In the infinite meadows of Heaven

Blossomed the lovely stars–

The forget-me-nots of angels . . .

Kalidasa says:

![]()

(Meghaduta: II–3)

Coleridge’s description of the ‘ancient mariner’

becalmed in the tropical seas–as idle as a painted ship upon a painted

ocean–has been justly famed for its simple felicity. It is apparently a

favourite idea with Kalidasa, for he presses it into service on a variety of

occasions. I shall choose one which happens to furnish an example of the fusion

of the painter in the poet. Dilipa is guarding the sacred cow on the slopes of

the Himalayas; suddenly, he hears the roar of a lion as it springs on the

helpless, cow his charge. But as he prepares to rescue the victim, he is

overpowered by a mysterious inhibition which the poet thus describes:

(Raghuvamsa: II–31)

The phrase ‘a baptism of fire’ has become trite by

repetition; But Kalidasa anticipated the phrase in describing the prowess of

Raghu:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: IV–41)

Indra beseeches the Supreme Being with all his

thousand eyes ‘like a collection of lotuses shaken by the gentle breeze.’ The

synchronising of the action suggests Wordsworth’s picture of the dancing

daffodils waving in the breeze. Wordsworth’s description of flocks in their

groups ‘forty feeding like one’ is another instance in point. Kalidasa speaks

of

![]()

Shelley’s description of the love of the moth for

the star is appropriate to Kama in the act of aiming his floral shaft at Brahma

himself:

![]()

(Kumarasambhava: III–64)

Said an English poet:

Ye meaner beauties of the night

That poorly satisfy our eyes,

More by your number than by your light,

You common people of the skies,

What are you when the moon shall rise?

Kalidasa puts it more succinctly thus:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: 6–22)

In a famous simile drawn from the current at the

Straits of Dardanelles, Othello speaks of the icy and compulsive course of his

revenge. The glamour of that passage is not in its geography, which is not

perhaps scientifically accurate, but in the emotion of the speaker. But

Kalidasa speaks of the course of a river blocked by a mountain, and making a

retrograde motion like the planets themselves:

![]()

(Kumarasambhava: II–25)

Similarly, Milton’s description of Vallambrossa

‘thick-strewn with leaves in autumn ‘–a description derived from hearsay, I

believe–cannot to the Indian mind at least, have the same suggestiveness as

Kalidasa’ picture of the Ganga over-crowded with flocks of swans in autumn.

Keats describes the sleeping Madeline as resembling

a rose that has shut and become a bud again. Kalidasa has many instances of a

similar description of the lotus by day and by night. It is the bright day that

brings forth the adder; Kalidasa warns that in clear lakes crocodiles may be

hidden from view:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: VII-3f)

The figure of the fly buried in amber goes back to

classical times. Lamenting over the dead Indumati, the bereaved husband says:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: VIII-55)

She is further described as

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: VIII-42)

which recalls Coleridge’s ‘horned moon with one bright star at the

nether tip.’

The mystic power of the human eye has been

recognised in the earliest works of our poets. Love at first sight is, I am

inclined to think, one of our ideas, which has made a westward migration. We

have a reference to Tara-maitri in our Grihyasutras. Two of the

loveliest, Elizabethan lyrics celebrate the power of the eye in love: “Drink to

me with chine eyes,” and “Tell me where is fancy bred.” Kalidasa has the same

idea:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XI–36)

where he describes the loving greetings of the citizens to Rama returning from his exile. Shakespeare’s ‘cloud-capp’d towers’ is an echo of

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XIV–29)

Coleridge’s description of lightning in the Ancient Mariner is

parallelled by

![]()

(Meghaduta: II–18)

where it appears like the glitter of a row of fire-flies.

Shakespeare’s description of the Dover cliffs has

many counterparts in the aerial view of the earth, the most famous of them

being also the most elaborate:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XIII–2)

The reduction of scale combined with the

preservation of proportion is extraordinarily vivid. Darkness is like

![]()

(Kumarasambhava: I–12)

a night-bird dwelling in a cave like Milton’s Melancholy.

It is a convention of our poetry that the ocean is

full of submarine fire as the mountains are full of precious gems. Coleridge is

the only poet who has described the phosphorescence of under-sea life in

picturesque terms. Kalidasa does not particularise, but he refers to the

phenomenon when he says:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: IX–82)

Shakespeare speaks of the one dram of evil that

o’erspreads all.

Kalidasa says:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XIV–38)

Infamy is like a drop of oil diffusing itself on waves of water.

One of the epic similes of Milton describes Galileo

at work with his new wonder, the telescope. Kalidasa describes the lens and its

properties with equal accuracy and appositeness:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XI–21)

Byron exulted that Freedom’s banner though torn

will still stream against the wind. Kalidasa has not only observed this small

detail of waving banners, but goes one better by recording the fact that they

are motionless on account of the motion of the chariot:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XV–48)

Macbeth is hailed as Bellona’s bridegroom–a

description that has led to much discussion as to its propriety. Kalidasa makes

no bones about it. He makes the goddess of victory a captive to be brought back

in triumph by Indra:

![]()

(Kumarasambhava: II–32)

Of sustained descriptions, one of the most delicate

is that which occurs in Canto IX of the Kumarasambhava of Agni in the

shape of a dove. For vigour and verisimilitude, it recalls Shakespeare’s description

of the hounds of Sparta in A Midsummer Night’s Dream or of the dew

lapped bulls in Venus and Adonis. The passage is too long to be quoted

here; but to those who know it and do not know Shakespeare, or rather vice

versa, the comparison is worth special study.

IV

I have till now dealt with only those passages for

which there seemed directly or indirectly counter-parts in the poets of the

West. My object in doing so has not been to plead for the consideration of

Kalidasa as a poet, but rather to show that in the whispering gallery of time,

voices are recaptured again and again, but so as with a difference, proving

conclusively how poets are of one breed, and how they react to their

inspiration in almost identical ways.

But there are other similes of Kalidasa for which

there cannot be parallels elsewhere. There is a residuum of uniqueness in every

poet, which gives him his character and individuality. There is a whole series

of figures in which Kalidasa deals with the invisible world, immaterial and imporlderable

values. These can have a meaning only in their contexts, and have to be studied

with them. But even of the purely imaginative quality of poetry, there is much

that cannot be translated without loss of the original bouquet. Such felicities

as

![]()

(Meghaduta: 11–35)

are delightful snapshots of life and nature. An English critic has tried

to make out that the idea of the side-glance of a maiden suggesting a string of

bees in a long line is a familiar one. But truth is that the maiden’s glances

are described, and bees are described separately; the peculiar combination of

the two is found only in Kalidasa.

Of similes which appeal to us as Indians, I shall

venture to mention a few before I conclude. In Sakuntala, there is a

famous description of a sense of joy tempered by memories of previous births:

![]()

(Sakuntala: Act V)

The same idea is found in a variant form in

![]()

(Kumarasambhava: I–30)

Shelley came nearest to the idea in his Ode to a Skylark

where he speaks of ‘our sincerest laughter’ being fraught with some pain

and our sweetest songs being those that tell of saddest thought. He, however,

does not account for the phenomenon as Kalidasa has done. The poetic use of

memories in their philosophical implications has been but slightly touched upon

by Vaughan in his Retreat and Wordsworth in his Intimation Ode.

It is not without significance that the idea is found more pervasively in the

work of many modern, living poets.

Kalidasa epitomises the Vamanavatara thus:

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–57)

A woman who looses her tresses twined with strings

of pearls:

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–63)

Indumati’s progress through the hall of Swayamvara:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: VI–26)

One of the crispest utterances of Kalidasa is in

the description of the abdication of Raghu:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: VIII–13)

Incidentally, it is the final answer to those who

have felt dissatisfied with Shakespeare’s killing of Lear, and who have sought

to re-translate him to the throne.

The monkeys going in search of Sita are compared to

the distracted thoughts of Rama himself:

![]()

(Raghuvamsa: XII–59)

It is also a peculiar feature of Kalidasa’s poetry

that he presses into service much valuable scientific lore in the guise of

mythological symbols. Thus the moon plays a very prominent part in his

descriptions; it is more than stage property, it is the lord of the ocean, of

herbs and of the thoughts of men. The comparison of rivers to maidens is

conventional enough; but Kalidasa gives it a fresh grace, a tremulous charm by

helping us to see the woman in the river. The ripple of water is like the

knitting of a beautiful maiden’s eye-brow; the eddies formed in a stream are

![]()

(Meghaduta: I–28)

My main aim has been to set Kalidasa amidst his

peers from the point of view of one of the easiest tests that can be applied to

any poet. May I say how refreshing, modern and urbane is the personality of

this man who speaks to us through a gap of time which has witnessed the rise

and fall of half a dozen empires and cultures! He saw life steadily, saw it

whole and preserved, withal, a divine sense of proportion. He had no

inhibitions, no frustrations and lived in the light of a thought which has

perennial vitality. I do not know how else we are to renew the springs of our

life than by bringing home to our generation the treasures of his mind and

spirit with all the strength of our awakened zeal.

* Based on an address delivered under the auspices

of the Madras Sanskrit Academy–Kalidasa Day on 7-10-43.