SIMPLIFYING NAGARI

By T. G. Aravamuthan,

M.A., B.L.

THE Nagari alphabet,–rather, syllabary,–requires

simplification. It is also easy to simplify. The simplification will be a

potent impetus to national progress.

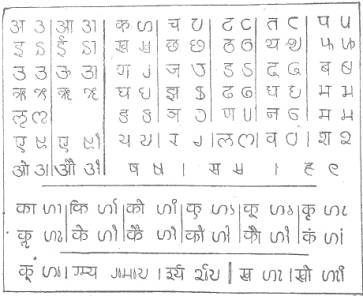

The accompanying Chart embodies an attempt at a

simplification which proposes the minimum of modification. The present and the

proposed characters are shown as pairs.

The majority of the characters have each a core–the

essential element,–garnished with a stroke on top and another at the side. Both

the strokes are needless. Knock these off and the cores emerge clear. Enlarge

the cores, where needed, to the size of the characters made of core and

strokes, and they become clearer still. The cores made up of fine combinations

of straight and curved lines, had been doomed to insignificance and ugliness by

the imprisoning strokes on top and at side: freed from those in cubuses, the

cores come out bold and beautiful.

The symbols in Nagari for consonants are often run

together into intricate combinations to make up conjunct-consonant symbols. The

integration of the characters is on a method: when, for instance, three

characters are to be integrated, the cores alone of the first two are taken and

affixed to the third which, however, is taken in full,–strokes and all.

Integration is, thus, effected by a certain amount of simplification. So, the

reader does not find the conjunct-character difficult to decipher, and the

scribe finds the character easy to write, notwithstanding transpositions in

positions. The printer, however, has to provide himself with core-characters in

addition to full-fledged ones and also to be at special pains to fit the

different characters together. This is no small handicap to the printer.

The principle of making one scriptorial unit

represent one syllable,–the basis of Nagari,–involves another complication,–the

representation of the vowels. The same vowel takes two different shapes,

according as it occurs initially in a word or it ‘animates’ a consonant. For

instance, the vowel i (as pronounced in the English word it) is

of one shape in writing it and of another shape in ti. Further, in the

latter case the symbol takes its place not beside, but above, the consonant

character. A variation is the case of a vowel like u (as in the English word put)

which gets, below the consonant character. This double change,–in form and in

position,–places no appreciable strain on the reader and imposes no special

strain on the scribe. But, it does add to the difficulties of the printer. He

has to compose two separate lines of characters and to adjust them meticulously

to give the reader one line of reading matter,–not to mention his having to

insinuate characters in almost impossible places.

The complexities of Nagari are, thus, more a

problem to the printer than to the reader or the scribe. The printer’s problem

will not arise if he has not to use types, for it is impossible to combine then

into complex syllabic characters. Were he using processes such as that of

photography, in which complex characters could be reproduced merely by

superimposing the various constituent characters, the syllabary will present no

difficulties. The present system of printing from type may at any time be

superseded by a different method, such as photographic reproduction, and, if

this happens, the present syllabic system will be found to be ideal,–with,

perhaps, a few minor modifications. But, such an event is generally considered

to be so remote that it is necessary to consider the problem of splitting up

the composite characters into the component elements so as to serve for good

types.

Let us first consider what, at first sight, looks a

simple solution,–the discarding of one of the two sets of shapes in which the

vowe1s occurred. The vowel-characters used initially may be used also for the

animating of consonants, but, as they are not distinguishable from the

consonants,–for they neither rise above nor fall below the line of

consonants,–there is bound to be a great loss in legibility: for there will be

disappearance of the vowel marks now affixed to the consonants, above or below.

Alternatively, we may eliminate the initial vowel characters and adopt,

uniformly, the superscript and subscript characters now used for the vowels

that ‘animate’ consonants. While these ensure legibility, their shapes have no

individuality, they having been designed merely as characters subsidiary to the

consonants. Separating them from the consonants and using them as independent

characters will lead to awkward results: the spaces below the superscript

symbols and those above the subscript ones will be gaps which, glaring in

themselves, will also divide two parts of the same word. A solution, however,

is not hard to seek; each of the super or sub-script symbols may be combined

with a vertical stroke which, covering the line of consonant symbols, will fill

the gap and give an appearance of continuity to the writing. An attempt in this

direction is illustrated in the chart. Slight changes in the shapes of the

vowel-marks have been effected to eliminate awkward resemblance’s.

The second step is to split up conjunct-consonants.

They are now formed by representing the subsidiary consonants in their

core-forms,–as already pointed out,–the last consonant alone being expressed in

full. It having been already suggested that the liberated cores of the

consonant characters may be accepted as equivalent to the full-fledged

characters, the conjunct-consonants may be formed by ranging the several

liberated components side by side. But, there is a catch. Each consonant

character in Nagari is really a character ‘animated’ by the vowel a: it has an a inherent in it. For example, the character for m is really

the character for the syllable ma, and that syllable is converted into

the consonant for m by the affixing of a mark. So, the ranging of two

consonant characters side by side, p and t for instance, will

give us, not pt, nor even pta, but pata. This difficulty

can be got over only by reverting to the system of core characters plus

full-fledged ones, or by adding a mark to the liberated core character to write

it down a consonant. Which device may be adopted depends on which will prove

more convenient. There is a general impression that animation by the vowel a

is commoner in Indian languages than animation by the other vowels. If this

belief is well-founded, the system of accepting each consonant symbol as

invariably animated by the vowel a,–that is, taking the consonant symbols k, g, for instance, as

representing ka, ga, respectively,–may well be retained, and a separate symbol employed for representing

what may be called the consonantization of the character. If there is no basis,

however, for the belief, it will be convenient to treat the characters is

representing only consonants. Statistics must decide the point: the printer

should not have to set up two characters if one will do.

The simplification effected by these slight

modifications brings about a great reduction m the number of types which a

printer has to keep stock of. From few hundreds it is brought down to a few

tens. Many of these modifications need not even be adopted in writing. The

modifications being very slight, no difference will be noticed if, in

writing,–as distinct from printing,–the vowel-marks are superscribed or

subscribed, as before: even the telescoping of consonants together for

conjunct-consonants may be reverted for the simpler combinations. There is no

need to compel the scribe to follow the printer, merely to satisfy theory.

But, even when simplified thus, the number of

characters is too many for employment in that great modern convenience,–the

type-writer. Here, again, the difficulty will disappear if the present crude

machine is improved on. This too appears, however, to be as far off as the

introduction of a method of printing that dispenses with the present form of

types. An attempt to bring down the number of the characters still further is,

therefore, worth the making.

Distinct characters for consonants of the series kh,

gh, ch, and so on, –what may be called the ‘aspirated’ consonants,–are

unnecessary. They may be dispensed with and a symbol for ‘aspiration’ may be

affixed to the basic symbols for the consonants, hard or soft. This suggestion

eliminates the ten aspirated consonants and effects a reduction by nine

characters.

The scheme as propounded here for the typewriter

will need only a total of about 38 characters,–about 23 for the consonants,

about 12 for the vowels–and about 3 for merely diacritical or symbolic

purposes. We secure an economy of characters greater than even the Roman

alphabet exhibits, and at the same time we retain the thoroughness which is the

characteristic of the Nagari syllabary. Even if we retain the characters for

the initial vowels and the ‘aspirated’ consonants, the aggregate number of

characters will not exceed 55 in number.

With 55 characters we have an alphabet that

deviates but slightly from the present syllabary, and with 38 characters

we have a system that deviates sensibly, but not radically,–not even

appreciably. In either case, the graphic system attains a legibility and

simplicity that are remarkable.

Refinements in design and in other practical

features may be introduced as further improvements. For instance, the symbols

for ‘animating’ vowels like u may be made to descend below the lower

line of the consonant characters so as to stand out more clearly. The

consonant–characters may be all designed to the size of an ‘em’, while the

vowel characters and the few diacritical symbols may be designed to the width

of half an ‘em’. It should even be possible to ensure that where a diacritical

mark and an animating vowel-mark occur side by side, they do not together

occupy more than half an ‘em’ in width. These devices will secure quite a

number of advantages, especially in typewriting. It should not be difficult to

provide that the carriage of a typewriter moves one unit for a consonant and

half a unit for an animating vowel, or for an animating vowel and diacritical

mark together. Such details, however, being for the technician, need not be gone

further into here.

It is hoped that this attempt,–which is all too

tentative,–at a simplification of Nagari will focus attention on an important

problem and will prompt efforts aimed at the bringing about of a much-needed

reform.