REVIEWS

Welcome the Moon rise–Forty

poems by Karan Singh. Published by Asia Publishing House, Bombay. Pages 43.

The Captive–Forty-six

poems by Shankar Mokashi-Punekar with a preface by Sir Herbert Read. Published

by Popular Prakashan, Bombay. Pages 71.

In Life’s Temple by

Vinayak Krishna Gokak. Published by Blackie & Son, Ltd. Pages 87.

The

late Prof. V. N. Bhushan, in his introduction to The Peacock Lute, an

anthology of poems in English by Indian Writers, edited and published by him as

long ago as in 1945, declared that ‘The Modern Renaissance that has been at

work in the country (India) during the last one century has been speeding up

the sentiments and sacraments of our race, and revitalising the life and

outlook of the people...our intellectuals realise the fact that India should no

longer dwell in splendid isolation as of old, but be an important factor in the

vast international organisation in the modem world…It is this unique national

and at the same time international experience that the modern Indian poets

writing in English express in their poetry.”

India

has since attained political independence, and recorded considerable progress

in her efforts–to modernise her economy to raise the standard of life of

her teeming millions, to take her proper place in the comity of nations, to

develop a national attitude and policy in international affairs, make her voice

felt in international sphere, and endeavour to make her own contribution to the

peace and progress of the human race.

Each

of the three volumes under review constitutes a no contribution to Indo-Anglian

poetry thus defined, by Prof. Bhushan, representing as it does, each in its own

way, the modern Indian mind, true in essentials to its ancient inheritance, and

at the time alive, and adapting itself, to the conditions of life in the modern

world. Each of the three authors has had a distinguished academic career and is

occupying a responsible position in his profession as well as in the public

life of the country. Each of them has already to his credit, a considerable

volume of poetic output, in English as well as in his Indian mother-tongue.

Herbert

Read, the renowned English critic, in a preface contributed by him to the

volume of poems, under review, by Dr. Mokashi, records his admiration for the

felicity with which the Indian poet expresses himself in contemporary English

idiom, and for the profound philosophy of life expressed eloquently in some of

his poems. The authors, of the other two of the three volumes under review,

deserve the compliments no less, with regard to the language as well as themes

of their poems.

Taking

the three volumes together, here is plenty and plenty of variety, of good

poetry, typical Indo-Anglian poetry of remarkably high quality. Here are poems

on the contemporary Indian scene and poems which reveal man as a pilgrim of

eternity; poems which explore the meaning of life in many contexts and in the

context of the poet’s personality; poems which are creations in English and

others which are translations (in the volume of Mr. Gokak) poems that are

romantic, with others that are modernist. In every poem, almost, the experience

communicated is genuine and significant, the philosophy of life expressed

consistent, characteristic of modern India and profound, the expression elegant

and

eloquent.

We

commend the publications to all lovers of English poetry in India and abroad,

with pride in the high quality of the intellectual fare presented in them, and

confidence that it will win the appreciation of all disinterested lovers of

poetry and genuine students of the modern Indian mind. The publications augur a

bright future for Indo-Anglian poetry in the times to come.

–M. SIVAKAMAYYA

Francis William Rain by

Keshav Mutalik. Published by the University of Bombay, University Buildings,

Fort, Bombay-I. Pp.207. Price Rs. 7.

As

a result of the British rule in India, a series of Englishmen came to India for

the service of the Company and later of the Crown. Many an Englishman tried his

hand at creative writing and hence we have a literature, which might harmlessly

be called Anglo-Indian literature. The great names are but few in Anglo-Indian

literature because a sense of exile pervades the bulk of the writing. The

Englishman looked upon India as the land that atomised his family–the

‘land of regrets’–and so the mood of sorrow and frustration never left

his mind. Thus, most Anglo Indian writers used writing to voice their grief and

bitterness, while there were others who thought that writing was after all not

in the ‘bond’ and took to it rather half-heartedly. It is, however, when we

turn to writers like Sir William Jones and John Leyden, Mrs. F. A. Steel and

Rudyard Kipling, Sir Edwin Arnold and F. W. Bain that we find Anglo-Indian

literature exceeding local limitations and achieving a measure of lasting

purpose and validity. It was these and a few other writers that could not

merely adjust themselves to the new surroundings, but cultivate a genuine love

for the land and its culture.

F.

W. Bain was professor of History and Economics and later Principal of the

Deccan College, Poona, for many years, in the early decades of

the present century. He was a great teacher who could bring an

original mind to bear upon his subject and whose teaching rose

above the narrow confines of syllabus and examination, and

became real and true liberal education. He was an administrator who wore his

authority lightly and was adored by his students and colleagues: ‘on this side

idolatry.’

Bain

had a versatile mind and a variety of interests, and his achievement too is

many-sided. He developed an intimate contact with Sanskirt literature and Hindu

mysticism. He wrote many stories, which read like Sanskirt stories in sensitive

translation, and the prefaces to these stories are a class by themselves in their

multi-coloured brilliance and serve to give us an idea of the stature of the

man and the nature of his art.

Mr.

Mutalik deals with the life of Bain at some length–birth and parentage

to last days–and seems to have taken enormous pains to secure his material.

He assesses the achievement of Bain as teacher and scholar

and the notable part he played in the contemporary cultural

life of Poona. The three chapters on Indian Stories, where the technique

and contribution of Bain are discussed, make interesting reading, and the

Appendices contain a number of letters which give useful insights into Bain’s

life and writings. The photographs are an impressive addition to the book and

the bibliography is good.

The book is probably documented to a fault and the quotations are often long and some are even repeated. One feels, however, that in spite or these overlappings and overloadings, a convincing portrait of Bain emerges, which is a good enough miniature of his colossal personality. The book is, on the whole, a laudable attempt in biographical writing.

–

L. S. R. KRISHNA SASTRY

Raft Ahmed Kidwai–A

memoir of his life and times–by Ajit Prasad Jain. Asia Publishing House.

Pages 130. Price Rs. 14.

Ministers

and civil servants, harassed by the perpetual problem of food shortages, must

be thinking now and then of the late Mr. Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, a successful Food

Minister, if ever there was one. But no one really knew the secret of his

success. Not even himself, perhaps, though he often took courage in both his hands

and did something that few others would dare to do. And luck used to favour him

in nine times out of ten. It was so with food decontrol in the early fifties.

Also with the Night Air Mail and quite a few other schemes that came like

rabbits from the magician’s hat. Rafi was a wizard in Indian politics, and the

author has been one of the staunchest ‘Rafians’ but even he succeeds (in this

book) more in testifying to this magic than in analysing its components.

But,

Mr. Jain tries his best. Rafi’s faith in human nature is something that draws

admiration. He was a shrewd judge of men, their foibles and all, without being

a cynic like much ‘wiser’ and more experienced men. Interesting anecdotes are

related in one chapter which is the most readable and revealing part of the

book. Knowing that a young man was a thief he would harbour him as a guest and

let him steal his watch besides! When the police haul him up in the court, he

ends up by giving evidence in his favour and getting him released. All this, because

he knew that the poor fellow was down and out and needed the help so badly. So

many lame dogs did he help over the stiles. His approach was essentially human.

His contacts with party workers, like those of Mr. Kamaraj, were intimate and

personal, and their loyalty to him was unshakable, He was far better in

lobbying than in lecturing, in getting things done than in outlining the

principles behind. Nehru and he loved each other deeply, without relying on

each other’s judgment. But they worked together smoothly and to great

advantage. He knew no feelings, of creed and community, which could be greater

than his country.

The

account given here of Rafi’s life and work by the author is rather scrappy and

disjointed, though presumably first hand and authentic in most cases. It bears

all the marks of hurried thinking, slipshod drafting and inadequate editing. It

is more likely to have been dictated to a steno than written in the author’s

study. It also alternates between a political biography and a topic pamphlet

that seeks to settle personal scores.

–“CHITRAGUPTA”

The Eternal Law by

Sri R. Krishnaswamy Aiyar. Pages 172. Price Rs. 4. Publishers: Ganesh & Co.

(Madras) Private Ltd. Madras-17.

Emanating

from the pen of Sri Krishnaswamy Aiyar, a disciple of the Head of the Sringeri

Mutt, and an author of the very popular books, Dialogues with the Guru, The

Call of the Jagat Guru, and Sparks from a divine anvil etc., this

book is of immense educative value to every student of Hindu religion, who

wants to have a clear idea of the basic principles of Sanatana Dharma.

“All

beings have a triple objective, viz., to live, to know, and to enjoy.” God, the

creator of this universe must have enunciated the means to realise these

objectives, and those means must be coeval with life and beneficial to all

beings of all times and climes. The enunciation of such means must also be

eternal and universal. The source of knowledge of these means can be none else

than the perfect knowledge of the omniscient God, whose teachings are found in

the Vedas which, being inseparable from Him, must also be eternal. So the Law

or Dharma enunciated in the Vedas is the Eternal law, otherwise known as Sanatana

Dharma.

Whatever is caused is impermanent and imperfect,

and if perfect existence, knowledge or happiness is conceivable, it cannot be

obtained. To have a thing, without obtaining it, can be possible, only when it

is available already with us. So the assumption that we have not got perfect

knowledge, etc., and that we must obtain them is inherently wrong, and this

basic misconception is known as Avidya. The eradication of this Avidya

is the aim of Sanatana Dharma.

The three bodies: Sthula, Sukshma, and Karana sariras, which are Avidya and its creatures, screen our perfect nature from ourselves. To destroy their screening capacity, three paths, corresponding to the three bodies are prescribed. These are Karma, Bhakti and Jnana respectively.

With

this background, the author explains in a thoroughly logical manner the

significance of all Karmas, Acharas, and restrictions, enjoined in

our sastras. The law of Karma and rebirth, the correlation of Karma,

Bhakti, and Jnana, are all thoroughly dealt with. Every point herein

is explained with a suitable example drawn from our everyday life.

Every

publication of Ganesh Company brings with it a fund of knowledge relating to

Hindu culture and wisdom, and this book is no exception. Every Hindu and every

critic of traditional Hinduism should read this book before

forming his opinion about Hinduism.

–B.

KUTAMBA RAO

Life World

Library–South-East Asia: by Stanley Karnow and the Editors

of Life. Time-Life International, Netherland. N. V. Pp. 160.

Hyderabad- The City We

Live in: Press Reporters’ Guild, IV-S-40, Fateh

Maidan Stadium, Hyderabad-1. Pp. 172. Price Rs. 5.

Konarka: by

Vijayatunga. Rs. 3. Publications Division. Delhi-6.

West Bengal and

Orissa: Rs. 4-50.

Utar Pradesh: Rs. 4-25 .

Bihar: Three

Rupees.–Issued on behalf of the Department of Tourism, by the Director,

Publications Division, Delhi-6.

Places

are among the most interesting things to read about, the writer responsible for

the book is one who knows his job. The human angle is very important here for

it is as much about people as about the places, rather more so. The human angle

is a specialty with the Life-Time group of journals, though the obvious slant

of the news magazine is often too blatant to be acceptable a dispassionate (in

so far as any man can be that) student of world affairs, This does not,

however, detract from the news service (purely from a technical, journalistic

point of view of smartness and efficiency) of the Time magazine or the

standard of photography set for itself by the Life International. All

these undoubted resources in news coverage and crack photography have been used

to good effect in the planning of the ‘Life World Library’, which has already

seen eight volumes or so on a number of the leading countries of Europe

(Russia, Germany, France, Britain and Italy), and Japan

and Mexico. The volumes sell on the photos in colour and in

black and white, though the letterpress is not negligible.

The

complex mosaic of races, religions and political hues that is represented by

South-East Asia is vividly brought before the reader in the latest volume

covering the subject. The impact of Western civilisation on a medley of

oriental cultures, the free mixture of racial groups and the juxtaposition of

different religions (Hinduism and Buddhism, Islam and Christianity) have given

rise to varieties of social experience which are not easy to analyse and far

from easy for a neat classification. On the top of all this comes the

confrontation of European political institutions of the liberal type with the

Asian brand of world communism. Tungku Abdur Rahman and President Soekarno are

symbols of the two different forces at work in this part of the world. Bright

snapshots are given of the life and struggle of the different countries in this

part

of the world by the reporter as well as the cameraman. While the political

undertones can profitably be ignored at times, the story in

general can be read with absorbing interest, after one has done with the

pictures.

Nearer

home we have many examples of the confluence of cultures that can aptly

symbolise the Indian cultural pattern of unity in diversity. The city of

Hyderabad comes in handy for the purpose, though we need to know more deeply

about its real personality, in addition to its history and geography. An

eloquent portrait of this city by M. Chalapathi Rau is one of the highlights of

the souvenir brought out by the Press Reporters’ Guild of Hyderabad

(“Hyderabad–the city we live in.”) Here is his masterly summing up.

“...It

is not the geometry of the place but the psyche that stirs people, and

Hyderabad must, while buzzing with the noise of modernity, nurse its past, the

vanished glamour of Golkonda and the more ancient austerities of the Buddhist

University, so real even in its ruins. Hyderabad is the gateway between the

North and the South, a nursery of culture amidst tranquil lakes, and if the

North and the South can meet there, it will be the second capital of India in

fact, if not in name.” Iswara Dutt recalls his close association with some of

the leading personalities linked with the destinies of the city and the State,

while B. Ramakrishna Rao sets the cultural tradition in its

historical perspective. There are quite a few articles by well-known writers on

other aspects of Hyderabad, besides many photographs of places of interest in

and around the city.

If

tourism is to make larger strides in India, one at least of the subtler

requirements would be the appearance of attractive literature on the subject.

Shakespeare’s tiny birth-place has possibly better and more booklets on its own

glories than any place of tourist interest in India.

There are, of course, formidable tomes on Ajanta and Ellora, but we want

popular and reliable hand books on these and other places in

India. Vijayatunga’s slim monograph on Konarka strikes the golden mean between

authority and readability. He does quote chapter and verse in his support, but

takes care not to clog his narrative with too many learned extracts. The

booklet is profusely illustrated. The neat and handy volumes on U. P., Bihar,

West Bengal and Orissa are also well-documented and attractively illustrated,

with photographs in colour and in black and white, as also some pretty line

drawings. They may yet be nowhere near similar publications available in the

West, but they are sure to be useful (the data are good enough) and good value

for the Price.

–D.

Anjaneyulu

The Dhamma Pada: Thanslated

by Irving Babbit with an essay on “Buddha and the Occident.” Pages 10+122.

Price $ 1.45. Publishers: New Directions Publishing Corporation, 333, Sixth

Avenue, New York 14.

The Dhamma Pada, a

book of all times, is a collection of 423 verses in Pali language, divided into

26 chapters. These verses, attributed to Buddha, contain the quintessence of

the Buddhistic philosophy. These ethical teachings have a universal appeal and

many of them are analogous to those found in the didactic and philosophical

literature in Sanskrit. e.g., “If a fool be associated with a wise man even all

his life, he will perceive the truth as little as a spoon perceives the taste

of a soup (p. 12). Self is the lord of self, self is the refuge of self,

therefore curb theyself, as the merchant curbs a good horse (p.56). What is the

use of thy mated locks, O fool! of what avail thy (raiment of) antelope skin?

Within thee there is ravening, but outside thou makest clean p. 58)”

In

the scholarly essay on “Buddha and the Occident” Buddhism is defended from the

assaults of occidental thinkers. Their mis-apprehensions regarding the

doctrines of Buddhism are removed, and it is presented in a clear perspective.

Buddhism is compared with Christianity, Vedantism, Stoicism, Sankhya and Yoga,

and the views of many western thinkers like Plato, Kant, and Hegel. The

theories of Behaviourists, Psychoanalysts and the moderns also are relevantly

brought in here in this context. Differences between Mahayana and Hinayana

are also briefly explained.

Buddha,

Babbit says, is comparatively free from casuistry, obscurantism and

intolerance. He is a critical and experimental supernaturalist and is humble

without being modest.

The

stoic is monist and the Buddhist is like a Christian, an uncompromising

Christian, a dualist, because of the contrast he establishes between the

expansive desires and a will that is felt with reference to these desires as a

will to refrain (p. 91). By exercising this quality of will a man may gradually

put aside what is impermanent in favour of what is more permanent and finally

escape from impermanence altogether. The chief virtue for Buddha is therefore

the putting forth of this quality of effort, spiritual consciousness (p. 91).

The stoic is theoretic optimist whereas Buddha is untheoretic and insistent

upon the fact of evil (p. 82).

Buddha’s

attitude towards the ‘Soul’ differs decisively from that of the Vedantists and

the doctrine of Plato. His objection to those who assert a soul and other

similar entities is not metaphysical practical (p. 84). Buddha dislikes mere

speculation.

Buddha

is not a saviour in the full Christian sense, because Buddha believes that Self

is the lord of self and gives prominence to Will whereas a Christian associates

this will with divine grace.

Babbit

explains the true significance of some technical terms like Nirvana, Karma, self-love,

peace, and meditation. Nirvana, he says, is extinction of desires.

Negatively it is escape from the flux and positively the immortal element (p.

96). Peace in which the doctrine culminates is not inert but active (p. 98).

While explaining the term meditation, difference between the views of Buddhists

and mystics is also explained.

In

the last few pages, Babbit deals with the question of war and peace between

nations. He says “Like the Christian, the Buddhist would begin at the centre–with

the issue of war and peace in the heart of the individual. Any conquest that

the individual may win over his own inordinate desires will reflect at once in

contact with other men...in the field of political action.” (p.111) and herein

is the significance of Buddha’s message to the war-torn modern world. We

heartily commend this book to all seekers of peace internal and external.

Vasucharitram (in

Samskrit): Translated from Telugu by Kalahasti Kavi. Editor: Dr. B. Rama Raju,

Osmania University. Pages 32+ 196. Price Rs. 4. Can be had from U. G. C. Unit,

Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Ramarajabbushana

(1500-1580) is a poet of unique fame. His Vasucharitra a Telugu

Prabandha was translated into Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada and into English also.

His mastery of slesha (double entendre) manifested in his narration of

two stories in one and the same breath, his talent in music pressed into

service in his handling of Telugu metres, and his poetic imagination and fancy

revealed in his delineation of sentiments, won him laurels from all critics.

Kalahasti

Kavi, who, according to the editor of this book, might have born about 1574 A.

D., translated this Vasucharitra into Sanskrit in verses interspersed

with prose. Like all other translators Kalahasti Kavi also improved upon the

original in some places, and attempted to bring out, in his translation, all

the charm of the dhvanis, sleshas and yamakams found in

the original, though he could not succeed in his endeavours in those places,

where that charm in the original is peculiar to Telugu idiom and words alone.

Bearing in mind the difficulties in the translation of a work full of sleshas

and yamakas, we must concede, Kalahasti Kavi succeeded in his

undertaking. A note-worthy feature in this translation is the poet, in many

places, could retain in his Sanskrit verses the yatis and prasas

that are peculiar to Telugu prosody. A chaste and lucid language, smooth

diction and a variety of metres–all these bear testimony to the high

scholarship and workmanship of the poet, which can be seen throughout his work.

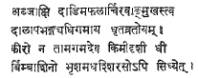

A few verses may be quoted here.

(3.182)

(3.70)

The

figure of speech and the double entendre in the original are aptly brought out

in the above two verses in order.

Our

praise goes to Dr. B. Rama Raju also for his critic introductions in English

and Telugu, and the care he has taken in editing this work. In the

introduction, he deals with the date and personality of the poet Kalahasti, and

compares the translation with the original in an exhaustive manner. The lacunae

in the manuscript are completed and the relevant number of the Telugu verse is

given against each Sanskrit verse facilitating ready reference of

the original thereby.

Our

commendations go to the publishers and the learned editor of this work. How we

wish this book is prescribed for study to the University students.

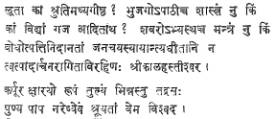

Sataka Saptakam: Translated

from Telugu into Samskrit by Sri S. T. G. Varadacharya, M. A. (Hons.),

Ex-Principal, Sri Narasimha Samskrita Kalasala, Chittiguduru and A. J.

Kalasala, Machilipatnam. Pages 133. Re. 1.50. Published by the Andhra Sahitya

Akademi, Hyderabad.

This

is a collection of seven satakams in Samskrit–(Sumati,

Bhaskara, Sri Kalahastisvara, Dasaradhi, Vemana, Sri Krishna, and Sri

Narasimha) translated from Telugu. Some of these are didactic while others are

devotional, though here and there, satire also is not lacking. Once these were

so popular that all school-going children in Andhra Pradesh had one or two of

these satakams on their lips.

The

translations are so well done that in all respects they not only preserve the

charm and beauty of the original, but also appear as though they were original

writings in Samskrit. The very lucid language, felicitous phraseology, splendid

syntax, sweet diction, choice use of verbs–all

these go to embellish the work in full. Mastery of verbal inflexion and

verbalism are reflected in every verse it is really a pleasure to read these

satakams, wherein various metres are also used appropriately.

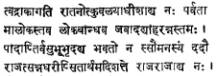

Two

verses cited here.

(p. 37) (p.

82)

By

publishing these translations the Sahitya Akadami also had done an unique

service to the Telugu genius and culture.

–B.

KUTUMBA RAO

NOTE

Please

note the following in the article A True Historical Approach Vs. The Marxist

Historical Approach to “Hamlet” published in “Triveni” for January 1966.

Page

16–opening paragraph (12th line)–The phrase ‘Collection of Writings’ refers to Shakespeare

in a Changing World (London, 1964), a book edited by Arnold Kettle and

published in the tercentenary year of Shakespeare’s birth. The Marxist

historical approach criticised in the article appears in Arnold Kettle’s essay

‘From Hamlet to Lear’ published in this book.

Page

19–The para beginning with the sentence: “Neither Hamlet nor

Shakespeare, in the year 1600, could resolve in action even

tragically, the dilemma of a young man...” should be understood to be a quoted

passage from Arnold Kettle’s essay.

Page 21–Read

‘has’ for ‘as’ in the sixth line from the bottom of the page.

Page

23–Paras 3 and 4 have to

be read as the quoted passages from John Lawlor’s The Tragic sense in

Shakespeare.