The Story in Stone of Great Renunciation of Nemintha

in

the

By

Dr. H. D. SANKALIA. M.A., Ph.D. (

We

are familiar with scenes from the life of the Buddha, particularly the Great

Renunciation, represented in numerous sculptures of the Graeco-Buddhist

school from Gandhata, Sanchi,

Amaravati and elsewhere in

The

story had become a classic as early as the 4th century B.C., for it is related

in the Uttaradhyayanasutra,* a

canonical work of the Jainas. Since then it was so

popular and sacred that as late as the 12th century A. D., Hemachandra,

the great poet-philosopher of

Neminatha, or Aristanemi as he was called before he became a Jina, was a prince who, some 5000 years ago, is supposed to

have lived in the town of

On

his way he saw animals kept in enclosures, overcome by fear and looking

miserable. Beholding them thus, Aristanemi

spoke to his charioteer. “Why are all these animals, which desire to be happy,

kept in an enclosure?”

The

charioteer answered “Lucky are these animals because at thy wedding they will

furnish food for many people.”

Having

heard the words, which meant the slaughter of so many innocent animals, he,

full of compassion and kindness for living beings, decided to renounce the

world and there and then he presented the charioteer with his ornaments and

clothes.

Everyone

including the gods, coming to know of Aristanemi’s

resolution, gathered together to celebrate and witness the Great Renunciation.

Thus surrounded, sitting on a palanquin, Aristanemi

left Dwarika for

With

but one exception, the story in the canonical work is faithfully represented on

a ceiling carved in the marble temple called “Lunavasahi”

built by Tejhpala, a minister of king Viradhavala of Gujarat in 1232 A. D., at Delwara on Mount Abu.

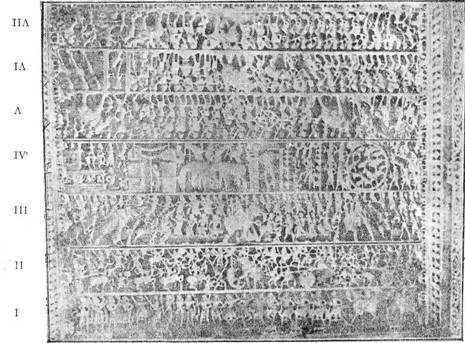

The

ceiling is divided into 7 horizontal sections. Each section depicts a part of

the story. Beginning from the bottom.

SECTION

I: Shows the dancers and musicians who led the marriage procession of Aristanemi.

SECTION

II: the battle between

SECTION

III: the musicians, army and clansmen.

SECTION

IV: (from right): first, the arrival of Aristanemi in

a chariot; second, animals tied for slaughter in an enclosure; third, the

marriage pandal, called ‘Chori’,

a square tent-like bower constructed with seven of earthen pots, supported by

stems of plantain trees, and decorated with festoons and garlands; fourth and

fifth, the elephants guarding the entrance of the palace and horse-stable;

sixth, gateway to the palace of Rajimati; seventh,

two storied palace, with the chamberlain announcing to Rajimati and her friends the arrival of Aristanemi.

SECTIONS:

V, VI, VII, face upwards. Chronologically first comes Section VI, then VII and

lastly V.

SECTION

VI: (from right) Aristanemi seated on a throne in the

midst of the assembly of gods and men, giving money and food in charity for a

year, before he became a Jaina ascetic.

SECTION

VII: (from left to right) first, a scene which cannot be exactly identified; it

shows Aristanemi seated on a throne attended by

fly-whisk bearers and others; second, Neminatha

seated in meditation pose and plucking out the hair in five handfuls.

SECTION

V: (from right to left) first, procession of gods and men

carrying Aristanemi on

We

may marvel at the strange happenings of the story, but not less marvellous is the art of the sculptor who has told it in

stone. His chisel has carved minute details with fulness,

vividness and a rare clarity. Every scene stands out in bold relief, endowed

with life and individuality. Behold the meek animals in the enclosure, and the

spirited elephant guarding the entrance to the

*An episode mentioned

in the canonical work but which is referred in the later works. This battle

took place because Jarasandha resented the death of Kamsa, his son-in-law, who was killed by

** Besides the art, it

would be worthwhile to compare not only this story but similar stories in Jaina literature, with those related in Hindu

(or Brahmanic) literature. For one thing, the story

in the Uttaradhyayanasutra enbles us to push back the traditional historic city

of