KALIDASA’S ARTISTIC VIGILANCE

By K. CHANDRASEKHARAN

Poet

Rabindranath Tagore posed a question which he answered himself. ‘What is Art?’

was the question, and his answer was as follows: “Should we begin with a

definition? Definition of a thing which has life-growth is really limiting

one’s own vision in order to be able to see clearly. And clearness is not the

only or the most important aspect of truth. A bull’s-eye lantern view is a

clear view, but not a complete view. If we are to know a wheel in motion, we

need not mind if all its spokes cannot be counted. In our zeal for definition

we may lop off branches and roots of a tree to turn it into a log which is

easier to roll about from classroom to classroom and, therefore, suitable

for a text-book. But, because it allows a nakedly clear view of itself, it

cannot be said that a log gives a truer view of a tree as whole”.

To

say, therefore, that Kalidasa’s poetic output

followed a particular mode or pattern of artistry would be confining his

personality within a narrow compass. The main aim of all great art being the

expression of personality, and not of anything abstract or analytical, it

necessarily resorts to the language of picture and music in the process of

self-expression. Maybe the result often is beauty. Still, we should not imagine

that the creation of beauty is the object of art, because it can only be the

instrument, and not its complete or ultimate significance. So Kalidasa’s culture and mind, more than his poetry, needs

our careful study. No doubt, it is only through his poetry that we can realise it. It must be an education to realise

it and seriously apply ourselves to it. By our sympathy and understanding of

the poet we can accomplish a state of harmony with what he created. We will

thus have achieved the highest education, which does not merely provide us with

information of him and his achievements, but makes us one with him, and one

with the path of wisdom, which, for him, lay in the harmonious pursuit of the

different aims of life and the development of an integrated personality.

Being

a poet first and last, Kalidasa has no use for the obvious and the commonplace

in life. In his art we get the selection of things without which life would be

defective in its sumptuousness and its vision. But sumptuousness does not

connote for him mere prodigality. Nature is prodigal, but art does not merely

copy it. The technique of all the arts is only the process of selection and

elimination. Luxuriance is not art; the jungle is luxuriant. The more refined and

vigilant the artist, the fewer things he needs for his effects. The results are

judged by the economy of the means employed.

A

poet of the genuine order never sets out to imitate nature in the literal

sense. For him art and nature are incommensurables, and there can be no

one-to-one correspondence between them. By an arduous effort at contemplation,

and of concentration, the poet does in fact free, himself from nature. In order

to gain some measure of expressiveness and effectiveness for the vision he

wishes to convey, he may deliberately use his liberty to distort or even misdraw objects which he sees around.

Now

Kalidasa is known as a supreme poet of love. No doubt his treatment of Sringara has earned for him the widest

popularity. Further, the theme of love has a natural appeal to a wider

audience. Because of its general appeal, love should hardly be deemed an easy

or unexacting study for anybody to suceeed in. Music

as an analogy will be quite to the point. In spite of its universal appeal, it

has never been to its votary a matter of ordinary effort at mastery. On the

other hand, it is in the field of music that there is an insistent demand that

its adherence to strict standards should be maintained, with its wider

appreciation and greater popularity. Sringara

Rasa, it is needless to add, has met with a similar fate, with its

indiscriminate treatment by all and sundry, down the ages. Either the sentiment

is debased into lewdness and sexiness, or its physical aspect alone gets

portrayed through elaborate description. Indeed, many a poet of renown has

indulged in it to the verge of depriving himself and the reader of all

sensitiveness to suggestion, which is the hallmark of true art. Kalidasa alone

among the classical poets in Sanskrit maintained a poise,

even when absorbed in setting out love’s amours or displaying eroticism. In a

way he alone touched the heart of intensity while being vigilant to restrain

the mind from wallowing in sensuousness. His culture and traditional upbringing

in the epics taught him that the supreme merit of love lay not in its physical

attraction but in its sublimation. Otherwise, his Sakuntala

should have remained unredeemed of her dishonour

consequent upon her passionate yielding to the King’s offer of marriage. That

which was not lasting as long as it was only physical became purified and

serene when burnt of all its dross, passing through the fire of separation when

rejected by the King. Suffering and sorrow are the twin tokens of God’s

benediction upon humanity in its upward march.

Parvati’s beauty of form

is spurned by the God, but the winsome constancy of her heart lays the

foundation for an everlasting share both in the body and the spirit of that

same God. The poem Kumara Sambhava has, even

in its narration, limitless marks of dramatic art so as to justify the Drisye-Kavya’s quality pervading that of a Sravya-Kavya. It is said of the Ramayana that

![]()

![]() however to the past its episodes belong, in

the present they seem to live. The art of Kalidasa, especially in the scene of Uma’s approach to God Siva, after his relaxation from

austerities, is resplendent with not only the graphic pictorial representation

of the whole drama in the magic of colours but with

liquid sounds woven into an ensnaring melody that soothes the ear and

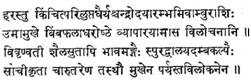

intoxicates the heart by turns:

however to the past its episodes belong, in

the present they seem to live. The art of Kalidasa, especially in the scene of Uma’s approach to God Siva, after his relaxation from

austerities, is resplendent with not only the graphic pictorial representation

of the whole drama in the magic of colours but with

liquid sounds woven into an ensnaring melody that soothes the ear and

intoxicates the heart by turns:

(God

Hara lost a wee bit of His balance of mind as He gazed at the bimba-fruit-like nether lip of Uma.

Even as the sea heaves at the sight of the rise of the full moon, His heart

expanded.

The

mountain-born also, by her movements and gestures, became more expressive of

her agitation. With down-cast eyes she stood, turning away with her arched neck

rendered more beautiful in that act.)

The

moment the attraction of the body gained a place in His heart, the God became

wary, and regained his normality, even as the poet seeks to restore in us our

equipoise which temporarily yielded to the phantom of delight visible in the

approaching of Uma towards Parameswara.

The beautiful drama to be enacted, with love’s inevitably unsmooth course,

seemed almost on the brink of accomplishment. With similar dramatic effect, the

poet stops the music of it all only to plunge us into the echoes

of sorrow’s wail over the death of Love.

In

the Scene in the Sakuntalam where the

King finds, to his heart’s fulfilment, Sakuntala left alone with him by her friends, the reader’s

anxiety to witness the intimacy of love in its mood of abandon

receives a check, as it were, when Sakuntala herself

warns the lover in his approaches:

![]()

(King of Puru race! restrain yourself; love-smitten as

I am, I am not free yet to give myself to you.)

Love’s

sublimation in Kalidasa’s treatment has few parallels

elsewhere. However much two loving hearts may seek union and keep us

expectant all the time to witness the consummation of their natural

inclination, the poet is careful to remind the reader that the culture

of India has been always distinguished by the superior quality of restraint in

her women. This is tellingly expressed in his Kumara Sambhava.

After Siva has been won over by the steadfastness of Parvati’s

penances to attain Him, he exclaims his readiness to espouse her:

![]()

(I

am your slave from now onwards.)

But

Parvati, true to her inborn culture, sends word in

private to him:

![]()

(To

Him, the soul of the Universe, Gowri through her companion sent word in

private: “My father, the King of mountains, must offer me. So let him be sought”.)

![]()

Again,

Kalidasa’s conception of true love as transcending an other considerations for those imbued with the highest

ideals is un-mistakably brought out in the Sakuntalam.

Marichi explains to Dushyanta

why the latter had to suffer a temporary loss of memory at the time of Sakuntala’s arrival at his court. Only a few moments back Sakuntala’s heart was disturbed by the offer of the King to

restore her lost ring. Her love could not brook such a flimsy token of love,

especially when its loss resulted in the King’s loss of memory:

![]()

(I

cannot be sure of this ring. Let my lord himself wear it.)

After

Marichi revealed that the curse of Durvasa was the chief cause of the King’s unfortunate

blankness of memory, Sakuntala feels a heavy burden

lifted from her heart as she says to herself:

![]()

(Thank

God, My Lord has not been without real reason for his rejection of me.)

The

sigh she heaves indicates that her love cannot be satisfied with anything short

of utter sincerity and truth. This dialogue is introduced by the poet so skilfully, only to reassure us of the sublimity of her

love. Hence also his artistic vigilance not to ignore one of the enduring

messages of this great drama.

Apart

from scenes of restrained love and suggestive amours, there are descriptions of

lustful meetings of lovers, as in the nineteenth sarga

of Raghuvamsa where ‘Agnivarna’s love-pranks demonstrate the poet’s powers of

realism. The requisite atmosphere is created for such an extravagant outburst

of eroticism. Still, it is in the very middle of such an orgy of sensuousness

that we come across a passage which Suddenly

brings him, and us as well, back to a sense of normality and rectitude:

![]()

(The

King himself played on the drum with his dangling garlands and moving armlets,

while the denseuses, having been drawn away to him,

transgressed the rules of gestural art, with the

result that they had to hang their heads in shame before their masters sitting

on the sides.)

The

poet’s conception of the highly spiritual quality of the art of dance in

While

Sringara is the poet’s main interest,

he is attentive to the other rasas whenever

they claimed him. Shoka, Hasya and Adbhuta have

all received their due recognition in his poems and dramas. Perhaps no other

poet has employed the Viyogini vrittam to better effect than Kalidasa, and yet none

else has so marvellously restrained himself from utter surrender to the mood induced by it. The

sidelights and observations emanating from him during the long wails of Aja and Rati relieve the tedium

born of unending tears.

If

the Viyogini has distinguished Kalidasa

from the rest of poets, the Mandakranta has

raised him to lofty heights. The murmur of metre has

only to be listened to with close-shut eyes. The music inherent in its elongated

lines has been rendered richer in symphony by the love-anguish of the separated

lovers. Kalidasa has made a cloud’s progress through the vast country of

![]()

Just

for a diversion, let us look at Kalidasa’s sense of humour which rarely rouses laughter but creeps gently into

our hearts so that we enjoy its delicacy and softness in the silence of our

inner thoughts. In the Raghuvamsa, Rama

abandons Sita to the forest while she is in an advanced state of pregnancy. He

calls Lakshmana to his side and orders him to carry

out his command. Lakshmana’s generous nature would

not let him do the slightest harm to Sita so long as it was within his power to

avoid it. To save Sita from discomfort while travelling in the chariot, he

yokes horses “not of a turbulent nature” to it. ![]() The poet thus makes us realise

the paradox of the situation; The resultant humour, especially as Sita’s

exile is imminent, is greater because of Lakshmana’s

attempt to save her from bodily discomfort in the face of the impending

catastrophe. There is also deep pathos in the situation. What poor satisfaction

to Lakshmana this, when he has been commanded to

execute the cruellest of orders!

The poet thus makes us realise

the paradox of the situation; The resultant humour, especially as Sita’s

exile is imminent, is greater because of Lakshmana’s

attempt to save her from bodily discomfort in the face of the impending

catastrophe. There is also deep pathos in the situation. What poor satisfaction

to Lakshmana this, when he has been commanded to

execute the cruellest of orders!

Another

humorous situation, very suggestive, is that of Matali,

Indra’s charioteer answering King Dushyanta

who wonders why the wheels of the aerial car of Indra do not touch the earth

when decending. He says:

![]()

(This

is the only difference between your honoured self and

Indra.) He means to elevate Dushyanta, in courtier

fashion, so as to make him feel no embarrassment by the difference in status

between him and Indra. On the other hand, the reader is aware that Dushyanta’s powerful aid had been sought by Indra, when the

vanquishment of his enemies had to be effected. In

the present context of the king’s return after a great victory over Indra’s foes, Indra’s prowess

could not be deemed greater than the King’s. It is an innocent joke of Kalidasa

at the expense of the heavenly lords. Normally this little piece of humour may escape notice unless scanned carefully.

Sanskrit

poets have employed upama or simile to

such a great extent that not only has it not shown off to attraction but often

as an adornment or figure of speech it has become superfluous or redundant the

way it is employed indiscriminately. Kalidasa, on the contrary, is justly

famous for his similes which not only impress us by their appositeness but also

by their power of elucidation and illumination of the upameya.

Speaking of one of the scions of the Raghu race, Aditi, whose welfare projects for his subjects were all

worked out to perfection without any publicity whatever, the poet compares his

works to the developing grain inside the corn though the world never notices

its silent process of growth:

![]()

(The

king’s strivings, with circumspection, after good works for his subjects bore

fruit, as grain within corn ripening, though all the while unnoticed by

others.)

By

a tiny simile, much more effective elucidation of the subject is achieved than

by an elaborate explanation. One of Tagore’s ‘Kshanika’

lines contains a similar thought. He says: “The night opens the flower and

allows the day to get thanks.” Really genuine workers do not care for any

advertisement of themselves. They always silently finish their labours without ever informing the rest of the world what

they had performed for the gain of others.

The

poet’s care and skill in employing Alankaras

may by themselves engage our serious study. Space and time forbid any

lengthy or exhaustive survey of them. Kalidasa never tires us out, nor does he

try our patience in any manner. Brevity and wit go hand in hand to sustain our

unflagging interest even in his narration of an epic like the Ramayana. In

Compressing within five sargas

the entire Ramayana, he arrests our attention by his wonderful

compactness as well as selection of incidents.

![]()

(Old age, through the

appearance of grey hairs at the temples, seemed careful to avoid being

overheard by Kaikeyi as it whispered into the King’s

ears: “Make Rama the ruler!”)

The

story of the frustrated coronation of Rama as Yuvaraja

is hit off so effectively with all the implications of court intrigue. The

re-telling of an elaborately detailed episode from the epic in the astoundingly

short span of a verse (sloka) convinces us of

the power of the poet’s control of material and his sense of proportion in

presentation.

Unless a poet knows

restraint, his art must suffer from lack of distinction in content and form.

Where one would write more, a single epithet or phrase or picture or imagery

does the work, with the enhanced value of gain in suggestion:

![]()

(While the sage of the

Devas spoke to her father, Parvati

standing near her father began with downcast eyes counting the petals of a

lotus flower she had brought for play.)

Without

saying in so many words how Parvati’s heart was

speedily collecting its own thoughts copcerning her

marriage with Siva, her preoccupation has been more expressively portrayed by

the picture of her counting listlessly the petals of a lotus. This particular

piece it has attained immortality at the hands of that arch-priest of Alankarikas, Anandavardhana,

as an undying example of Bhava-dhvani.

Leaf

and flower, dewdrop and glow-worm, lightning and rushing waters, deer and

peacock, have all invested the poet’s heart with a peculiar affinity with all

God’s creation; and his poems and dramas are replete with the frequency of

their appearances even as that of human characters. A truer Advaitin

than he has not trodden this land of ours. His natural claim of kinship

with-them makes no distinction between the tiniest, lowest or highest. If he

turns his eyes to the wavelets in the river, he cannot but fondly trace their

close relationship with the intermittently throbbing eyebrows of a sweetheart.

If he admires the heavy burden of a peacock’s feathers trailing on the ground,

his immediate reaction conjures up for him the dark flowing tresses of a

damsel. If Sakuntala approaches a creeper and seeks a

parting embrace from its encircling arms, she does it in no patronising

manner but quite as it behoves an intimate companion:

![]()

In

the anguished tidings of the Yaksha to the

cloud-messenger, he scarcely forgets the tender Mandara

tree.

![]()

(Where in the garden you will find the young Mandara tree, reared like a foster-child by my Beloved,

which, on account of clusters of flowers bending the boughs, is easily reached

by our hands).

Arts and sciences too make their

welcome entry into his comprehensive ken. Music, both vocal and instrumental, enthuses him. The Veena and the Mridanga are recognised by him as

unrivalled for their charm. Dance and painting are his constant rejuvenators.

Especially the latter’s summation is reached in the unfolding of an entire play

devoted to the message of love through the most expressive of languages, the Abhinaya. The arts are not merely drawn upon

as aids to his fancy, but as very potential factors in their interplay on life.

Kings and sages, merchants and soldiers, danseuses and love-messengers, house-holders

and children, foresters and fishermen,–all move about functioning naturally in

his world. They subserve the very purpose of a rich

and complete life which the poet envisages for one and all. He draws upon them

all to get life on earth knit to Life Supreme.

Valmiki and Vyasa, no

doubt, are great artists, with material as extensive and varied as the universe

itself. Yet they comprehend everything, not with a look that holds and guards

this, that, or the other detail or scene, but which from first to last remains

pure contemplation, ![]() Kalidasa comes very near them in his vision of

life always as whole and never compartmental. His poetry, like theirs, is Bharata-Varsha. It is the ripe fruit of his devotion to

Indian culture and age-long tradition. It is the soul of a great people, not

merely the emotion of a single individual. It is a systematic view of life, not

merely a poetic mood. It is an enveloping culture, not merely a tune. It is an immortalising theme in humility, never a mere poetic interpretation.

Kalidasa comes very near them in his vision of

life always as whole and never compartmental. His poetry, like theirs, is Bharata-Varsha. It is the ripe fruit of his devotion to

Indian culture and age-long tradition. It is the soul of a great people, not

merely the emotion of a single individual. It is a systematic view of life, not

merely a poetic mood. It is an enveloping culture, not merely a tune. It is an immortalising theme in humility, never a mere poetic interpretation.