The Art of Chughtai

BY G. VENKATACHALAM

Islamic contribution to Indian life and art is as vast as it is varied; the richness and the composite character of Indian civilisation are the result of the mingling of many races and cultures, the two most important of them being the Aryan Hindu and the Semitic Arab. India and Persia have mutually influenced each other from the dim past of their history, and the Moghul conquest of India was the culmination of their cultural contact and artistic affinity. From Bihzad to Chughtai, the history of Indian painting is the story of this mutual ‘give and take’; and the art ideals and art forms of these two countries are not equal and opposite, but different and complementary.

The Hindu art was virile, aggressive, awe-inspiring and masculine, while the Islamic art was tender, graceful, persuasive, pretty, pleasing, and feminine; the Hindu art is idealistic, other-worldly, symbolic, ornate, and massive, while the Islamic art is realistic, courtly, aesthetic, pure, and decorative. Elephanta and Ajanta exemplify the former; the Taj and Mughal Miniatures exemplify the latter.

Modern Indian artists unconsciously reflect these complementary characteristics in their art. Nandalal Bose is the typical Hindu artist, and Chughtai the typical Muslim artist. Both are Indians, great and good as artists and men, and both represent the two respective styles at their best. Chughtai's contribution to modern Indian painting is as significant as either Nandalal's or the Tagore brothers’, and he too, in his own way, is one of the pioneers in the renaissance of Indian art.

Chughtai's paintings bear strongly the impress of his personality, gentle, generous, sensitive, and romantic; and though his individuality is obvious in his works, yet there is no gainsaying the fact that his art is rooted in Persian tradition and outlook. In the free flow of his lines, in the soft shades of his colours, in the exquisite finish of his brush, in the mannerisms of his subjects, in the draperies and other decorative elements, and in the general atmosphere of his pictures, you see clearly his Persian feeling and impulse. This is but natural, as he is a lineal descendant of one of the Moghul artists who gave to the world such gems in architecture as the Pearl Mosque in Delhi and the Jasmine Tower in Agra. Chughtai's architectural backgrounds in his paintings reveal his heritage.

His eclectic nature makes him an artist of universal appeal. He is as sincere and sympathetic in his studies of the Hindu gods or heroes as he is in his studies of Persian poets or Muslim fakirs, and his pictures of Radha and Krishna are as delightful as his pictures of Leila and Majnun. He draws the figure of Arjuna with as much understanding and fine feeling as he draws the figure of Aurangazeb, and to him the play of Holi is artistically as significant as the festival of Ramzan. His recent visit to Europe and his personal contact with the art and artists of the countries he toured in the West have happily enlarged his vision and enriched his knowledge and technique, and his future works are bound to be of greater variety and wider appeal. He is not only a great painter but a skilled craftsman also, who can cut and carve and even print and publish his own books. His Muraqqa-qu-Chughtai is a splendid specimen of book production, as beautiful and excellent as any published in the West, all executed single-handed by the artist with just a small printing press and a few implements in a tiny room in his house at Lahore. His illustrations of Ghalib and Omar are a class by themselves.

In the two pictures reproduced in Triveni we see his genius in two different moods. They are in his best style and reveal a new development in his art. The coloured reproductions, as is inevitable, do no justice whatsoever to the originals and do not convey their exquisite colour feeling and the, richness of their composition.

"Hermit" (frontispiece) is a delightful study, in pink, white and gold, of a young ascetic who has seen better days and who has now renounced everything in the quest of Truth. With a staff in his hand and a far-away gaze in his eyes, he sits dreaming. His dark curly hair, large tranquil eyes, thin straight nose, small sensitive mouth, long arms, tapering fingers, and his flowing robes and conical cap betray the artist that has become a hermit. A straightforward study of a Sufi soul is this. This picture reminds one of Bihzad's portraits in its directness, simplicity, and colour sense.

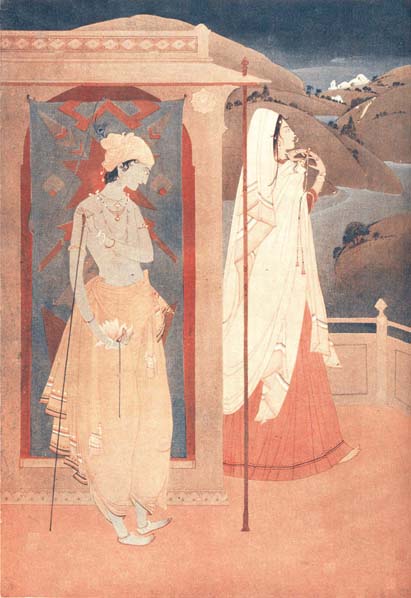

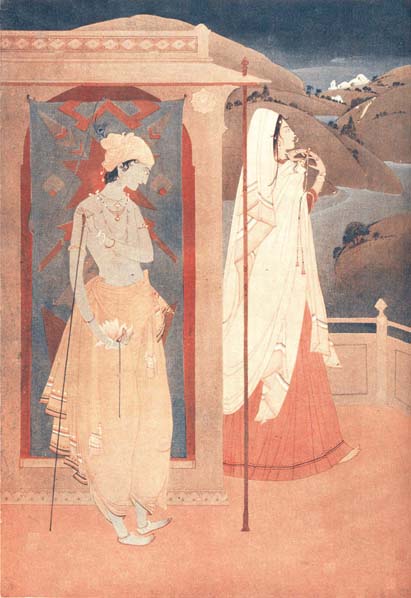

SUNDER VALLEY

"Sunder Valley" is lyrical in its nature and appeal. Youth and Beauty stand, shy and romantic, at the threshold of life's joyous adventures. A lovely valley, with undulating hills, tree-covered meadows, rushing rivulets and nestling white villages, spread out before them, challenging them to come out of their narrow prison walls of marble palaces and towering terraces, to taste the simple, natural pleasures of a free and unfettered life of the wilds. A far-fetched interpretation, the artist might say, to a simple study of Radha and Krishna in one of their playful moods! This sweet picture is, in its theme, treatment, setting, background and lyrical nature, a little reminiscent of a Kangra miniature.