Sittannavasal Frescoes

BY M. S. SUNDARA SARMA, B.A.

The earliest well-known examples of the art of painting in India have been so far confined to the northern border of South India and are as varied in their technique as in the subjects they treat about. Those of the Ajanta caves are of the greatest extent, though only a fraction of the whole remains now to be seen. Most of them are considered to be of Buddhistic origin, because one or two of them are labeled as such or because a few of the Jataka stories are conveniently read in them. Whether the whole of the paintings are really so is to be doubted, especially because the later followers of Lord Buddha, in their overzealous endeavour to proselytise, labelled and adopted so many things that had existed in the country. Whatever that may be, there is no questioning the fact that there is not one central or dominant key for the interpretation of the scattered paintings in any of the caves. It cannot be due entirely to the loss of most portions of them. At Ajanta the art covers a long period of time running up to centuries, and as such the treatment and the subject matter have been very varied and divergent. Though the technique of them all was alike and indigenous, the contents thereof are neither strictly in unison with the notions of art as depicted in Indian architecture and sculpture, nor in accordance with those dhyana slokas or contemplative verses of the Indian Shilpa Sastras. They are no doubt depicted with a degree of proficiency unmatched in Europe till about the fourteenth or fifteenth century. Though a joyful contemporary life and manners are depicted therein, the deeper surgings of the art of the law which sway its architecture and sculpture, whereby Indian art really becomes a microcosmic concept of Cosmic aspects, are clearly absent from them, except indirectly here through a phase of the life of the Lord Buddha, or there through depicting a particular leela of the Lord Krishna, one and the same incident very often being interpreted by the Buddhist or the Hindu each according to his own way! The high spiritual symbolism, the Cosmic idealism and the deep content of real Indian art are alike absent in any of them. So much so, that criticism saw therein a ‘frank naturalism’ a characteristic that was solely attributed to the so-called ‘Buddhist art’ within which category these cave paintings were summarily incorporated irrespective of the subject matter of the compositions.

That this mature art of painting could not have been confined to this particular locality has long ago been wisely recognised, because of the few traces of frescoes found here and there in the country, and because of the innumerable literary references to the existence of picture halls or galleries. There were really no other visible records to show us as to what extent and in which direction the art had prevailed really in ages long gone by. Criticism was in doubt whether to trace the art from Tibetean banners or Central Asian walls till it rested with the satisfaction of going out elsewhere than this country!

Being the most perishable of the fine arts, it had to submit itself, for want of visible records, to the whims and fancies of criticism till it found a fortunate discoverer in Mr. T.A. Gopinath Rao, the learned author of Indian Iconography, who in his energetic search for Pallava inscriptions on rocks, chanced to come across some old relics of frescoes at Sittannavasal in the year 1919, just a century after the discovery of those at Ajanta.

"These paintings are perhaps, as old as the shrine and are a fairly good state of preservation, and need being copied fully", wrote Mr. Gopinath Rao to his friend and collaborator, Prof. G. Jouveau Dubreuil of Pondicherry, who, on his part, went over, to the cave early next year and saw that from an artistic point of view, the remains were similar to those of Ajanta paintings and that they were very remarkable. He forthwith drew the attention of the public, by means of a leaflet in which a rough tracing of the outline of one of the dancing figures only was given, as the Professor's photographs of the paintings, though taken with care, were unable to give satisfactory results.

Realising only too well the real value and importance of the discovery, the artist in me hastened to the spot and stood face to face with the precious old relics early in October 1922. Before leaving the cave for the time being, I made careful copies, though smaller in scale, of the two dancing figures and a head on the pillars as well as a portion of the panel found intact on the ceiling of the cave. My copies were exhibited at once before the elite of Pudukottah during my lecture in the College there, when the value of these paintings was duly pointed out and emphasised. The Madras Mail Annual of 1924 promptly purchased and published beautifully in colours one of these dancing figures with a note about the cave which I had sent at Dr. Cousins's request.

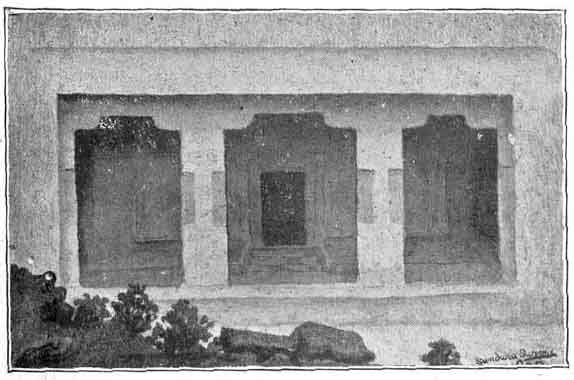

Outer view of the Sittannavasal Cave

The Ajanta frescoes though discovered in 1819, failed to attract attention until 1843 when Mr. James Ferguson persuaded the Directors of the East India Company, to copy them at public expense. The copies that were made by Mr. Gill in pursuance thereof were unfortunately lost. Subsequent copies too, by others, shared the same fate. Only between 1872 and 1885 when Mr. Griffiths, in collaboration with his pupils" of the School of Arts in Bombay, made elaborate copies and published the now-famous atlas folio volumes, some adequate justice may be said to have been done to the Ajantan discovery.

Lest a similar tale may not be told of the newly discovered paintings at Sittannavasal, I was preparing, so far as an individual could prepare, to go to the cave duly equipped, to make copies of the whole of the Visible paintings. In the meanwhile, in addition to the reproduction of one of the figures in the Mail Annual of 1924, I was exhibiting my copies at various places I went out lecturing, and Dr. James H. Cousins of Adyar took with him in his North Indian tour a set of my copies, exhibiting them and talking about them at several important places. Another Madras paper, The Daily Express also published an article by me on the value of these paintings, accompanied by black and white reproductions of all the copies I had then made. While in the North, Mr. N. C. Mehta had my copies, that were exhibited at Lucknow by Dr. Cousins, traced by an youngster of the Bengal School, without either my knowledge or that of the Doctor who had exhibited them. He reproduced them in his book Studies in Indian Painting, giving the credit to the stealthy copyist of my pictures! Mr. Mehta has, however, sent me later a letter of apology, not realising that apologies alone do not mend matters always. But I was content that by some means or other the old frescoes had been brought to greater public attention.

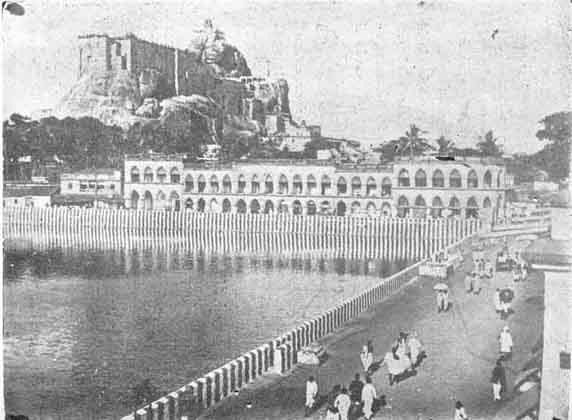

The Rock Fort, Trichinopoly

Through the kind influence of my friend, Dr. K. N. Sitaraman, who was then the Vice-Principal of the College at Kolhapur, the Chief of Aundh took interest in the copying of the frescoes at Sittannavasal, and placed very generously at my disposal a munificent sum that enabled me at once to go to the cave fully and duly equipped. Early in the year 1926, I started out for the cave to do full justice to the paintings by copying carefully to scale and tone all the visible portions of the old frescoes. Madame Bermond, an accomplished French painter, came along with me to the cave and was of immense help to me during the few days that she kindly remained with me after seeing the old relics. I continued my stay there for several weeks more till I finished the work for which I went over there.