THE MESSAGE OF “RAMAYANA”

TO THE MODERN WORLD

Dr. I. PANDURANGA RAO

RAMAYANA,

THE WORD and Ramayana, the work are both marvellous, immortal and unparalleled creation of a Master Mind, sagacious in vision,

soft and sophisticated in speech and silently eloquent in message. Ramayana

is neither a story nor an epic, but an everlasting and telecasting lighthouse

that has been working ever since the word has acquired vision in the history of

Indian literature, culture and philosophy as a transformer converting dazzling

darkness into leading light. It bears testimony to the Vedic verdict that a

single syllable can serve as a source of stupendous splendour (aksharad-deeptiruchyate).

This celebrated work has, therefore, been very appropriately described as a

poetic version of the Vedic vision (Vedah prachetasadasit sakshat

Ramayanatmana).

The

word Ramayana, like the name Rama, has a world of significance and conveys in a

compact and concise form the purport of the work Ramayana. It is a

compound word formed with the combination of two component words – Rama and

Ayana. Rama is the main character in the composition and ‘ayana’ (meaning march, movement or abode) is the characteristic

feature of this pivotal personality. The central theme of Ramayana is

the well-designed and purposeful March of Rama in search of Good – good

conduct, good heart, good will, good words and a good world worth living in,

Rama is, where good exists. That is his abode and that makes him mobile.

Ramayana is, therefore, an inspiring and instructive description of the graceful March of Rama.

The word Ramayana also presents a judicious combination of static tranquility and dynamic adaptability. The word ‘Rama’ is derived from the root ‘Ram’ meaning “to get absorbed” and “ayana” from the root. ‘E’ meaning “to move on”. In Rama we find both these traits in rational proportion, making him a complete man–the Man of Valmiki.

The

word “Ramayana” was so thoughtfully coined

by Valmiki that it includes the Woman as well as the Man as conceived by the

Master. Raamaa the feminine form of Ram stands for Sita and so the word

Ramayana, split up in two ways–Rama+Ayana and also Raamaa + Ayana – denotes the

concurrent and coordinated March of both Rama, the son of Dasaratha, and

Ramnaa, of offspring of Janaka. Valmiki uses the word “Rama” to denote Janaki

in a number of places. Thus the concept of equal importance to man and woman is

inherent in the very title “Ramayana”. In fact Valmiki refers to his work as

the great grand story of Sita (Sitaayaascharitam mahat). Goswami Tulasi

Das used the word “Charitam” very appropriately in naming his celebrated work “Ramacharita

Manas”. Incidentally, the word “Charit” used by Goswami also has the

connotation of “movement” or habitation, and the Saint has placed his “Manas”

at the disposal of his Lord to inhabit. That is why he seeks the blessings of

Sri Ganesh to ensure that his “Manas”, the innermost conscience surging with

vibrant waves of devotion, becomes the blissful abode or habitat for his Lord (Basahu

Rama Siya Manasa More). Thus the “Ayanam” of the Adikavi has been wisely

appropriated by the medieval saint-poet Tulasi as “manas”, the forum for the

sportive manifestation and the characteristic deeds (Charitam) of his

Lord. We are, therefore, fully justified in establishing a link between the two

great souls when we say Valmiki is reborn as Tulasi (Valmiki Tulasi Bhayo).

If

Rama was an embodiment of Dharma (Ramo Vigrahavaan Dharmah), Goswami Tulasi Das was Devotion personified. Devotion or

Bhakti is the main spirit behind this immortal work which Valmiki chose to name

“ayanam” to stmt with. It was indeed a big “start” which took innumerable forms

not only throughout the country of its origin but also beyond its physical

boundaries.

It

was rightly said about this magnificent

work of universal appeal that it would spread far and wide – wherever humanity

exists, rivers continue to now and mountains stand firm. In all the Indian

languages, we have a profusion of great epics based on the theme of Ramayana.

To name a few, Kamba Ramayanam in Tamil, Toravai Ramayanam in

Kannada, Ranganatha Ramayanam in Telugu, Adhyatma Ramayanam in

Malayalam, Bhavartha Ramayanam in Marathi, Giridhar Ramayanam in

Gujarati, Krittivasa Ramayanam in Bengali, Balaram Das Ramayanam in

Oriya, Madhava Kandali Ramayanam in Assamese, besides hundreds of works

in Sanskrit have given multiple colour and flavour to this fascinating theme

which has become an integral part of Indian thought and culture.

Bhakti

(devotion), Shakti (spiritual power) and Rakti (popular appeal) are the three main

motivating forces which have driven home the message of this time-honoured composition ever since its genesis and hopefully it

will continue to provide inspiration, guidance and direction to humanity in the

centuries to come. Valmiki being a pioneer in the field maintained a marvellous

balance between the three, while the later poets chose one of them as their

main stream and incorporated the other two as tributaries. For instance, Bhakti

is the main stream of Ramacharita Manas, while Rakti is that of works

like Ramachandrika of Keshav Das. Whatever the main thrust, almost all

the exponents of theme deviated from the original course of events depicted by

Valmiki. But this deviation has only added dignity and magnanimity to the

original theme as the message conveyed and intended to be conveyed is the same

throughout.

Valmiki

excels more in silence than in speech as far as his message is concerned. He

speaks through his characters who also often choose to be less eloquent in

order to be more expressive. Sometimes even inanimate objects express

themselves better than articulate beings when they feel the solemn touch of the

Sagepoet (Kavyarshi). For instance,

when the sage stands on the bank of the river Tamasa watching the whispering

waves, the crystal clear water seems to be suggesting to the seer that the

human mind, too, should try to follow the fascinating movement of river-water.

The poet gives a secular expression to this incomprehensible voice of the river

thus:

![]()

(Look, my dear Bharadwaja! Just listen to the pleasant and placid water flowing with graceful gait like the pure conscience of a gentle person.)

While

saying this to his intimate disciple,

Bharadwaja, the sage must have had, at the back of his mind, the qualities of a

perfect man narrated by Narada only a few days back when he was

approached by the sage to find out whether a man of all the desirable

qualities ever existed on this earth.

Narada says in clear terms, “Yes, such a man exists–does exist – right now and here, with us, in us and around us,”

and points out Rama, a man of great potentialities, a rare specimen of

righteousness personified, and an admirable admixture of wisdom and strength,

courage and compassion, conviction and consideration, dedication and detachment

and finally ultimate reality and immediate justice. The sage-poet Valmiki finds

all these qualities reflected in the reverberating rivulet Tamasa. Thus the man

of vision identifies the man of mission whose thoughts, actions and

expressions are themselves lasting messages for the vast mass of humanity.

As

the basic concern in all these qualities

and attributes is humanity, Valmiki finds that the man of his vision is one

whose human virtues make him and his admirers forget even the intrinsic

divinity in him. Thus the primary message that Ramayana has for the

humankind as a work of art is that the basis for all human resource development

is man-making. Dignity, decency and decorum are the basic virtues which go to

make up a man or a human being. If the human being is human in the desired

sense of the term, the world is worth living in. Otherwise all the material

prosperity and scientific advancement will work against the interests of

humanity and the purpose of life itself gets defeated.

Delighted

to find an ideal human mind reflected in the river water, Valmiki takes a walk

on the river bank. He looks around. He finds a couple of birds sitting on the

branch of a tree engrossed in their sweet and soulful moments of joy. Suddenly a hunter shoots down the male-bird, separating the

mates for no fault of theirs. This shakes the tender heart of the sage and his

anguish bursts out in the form of a verse. This is the famous verse which is

supposed to have converted deep agony (Shoka) into a fine poetic

expression (shloka); an emotional

outburst into an elegant verse. The very starting of the verse ‘Ma Nishada’,

(Oh! hunter thou shall not) has a startling and stimulating effect which

has had a lasting impact on human heart right from the Vedic or epic age down

to the modem age.

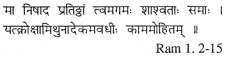

The oft-repeated verse firmly seated in the hearts of all lovers of poetry and expressing compassion deserves a reproduction:

(You

cruel hunter, thou shall not live for long with respect and rapport as you have

mercilessly massacred one of the two

innocent creatures depriving the pair of their legitimate personal pleasure.)

The

moments that followed were momentous not

only for the poetic community but also for the entire humanity as they have inspired

innumerable votaries of poetic expression and conveyed the basic message of non-killing

to the human race. This is all the more relevant to the modem world, miserably

caught in a mess of mad and misdirected man-killing day-in and day-out. What is

more significant to us today is that this message voiced by a magnanimous heart

condemns not only man killing but all killing causing any imbalance in the

organisation of the environment in which we are fortunately alive in spite of our

meaningless animosity towards our fellow-beings, and the nature that nurtures

us. This utterance made by the sage-poet in a moment of grief coupled with

compassion for the cosmic community has a world of significance for the citizens

of the world who are bound to deprive themselves of the right to live if they

do not care for others who also enjoy this right by law of nature and natural

justice.

The

place of women in modem society is another common topic which finds a realistic

approach in Ramayana. The very title of the story Ramayana places

man and woman (particularly Rama and Sita)

on the same pedestal giving them equal status, dignity and importance. This

has been discussed earlier from the semantic point of view.

If

we carefully analyse the course of events that brought elevation and elegance

to the ideal couple – Rama and Sita – we find that each one of them excels the

other in all respects – in physical

beauty, mental makeup, metaphysical

outlook, spirit of service and sacrifice, concern for others even at the cost

of personal comforts, indifference towards earthly pleasures, integrity in

thought, word and deed, unshakable faith and trust equally reciprocated by

both, and above all a kind heart for the humankind even in the face of unkindness

and unreasonableness.

In

some respects Sita excels Rama. Rama became great because Sita was greater. Her

readiness to leave for forests along with her husband, the forbearance she

showed towards all atrocities committed on

her, not only by the evil-minded enemies but also by her own kind-hearted

husband reflect her guiding principle in life – silent suffering with strong

determination to stick to the path of righteousness. This attitude towards

life did reward her and her husband too and made their life story immortal and

their message universal and eternal. This is what Sumantra says while consoling

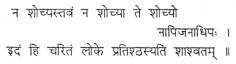

King Dasaratha and the grief-stricken Queen Kausalya:

(There

is nothing to worry about your dearest son and devoted daughter-in-law. They

arc quite happy because they have invited this course of suffering on their

own. They are treating pleasure and pain alike. Therefore neither you nor the king should be distressed at this

turn of events which is bound to make a mark in the history of mankind while

endurance takes care of the trivial

troubles and turmoils that we are facing now.)

These

words of Sumantra have a Mantric

(enchanting) effect not only on the aged parents but also on the age-old

humanity as they provide strength-mental and spiritual to the majority of the

suffering community in the world. Suffering is not a curse, but a crude form of

penance gifted to a selected few who are designed and destined to distinguish

themselves as the commissioned counsellors for human dignity – “Pratishtha”.

It

may be recalled that the word “Pratishtha”

occurs for the first time in the very first utterance of the sage Valmiki (Ma

Nishada Pratishtham Twam). The same word repeated here as spoken by the

royal charioteer Sumantra needs to be compared and correlated with its earlier

reference. What is “Pratishtha”? May be, that is the essence of life–the net

product of all pleasures and pains of life, what remains after everything in

life disappears. All that happens fades away but the feeling left by

these events does remain ultimately. This “ultimate” serves as an ultimatum to

those who try to tread the path of temporary and temporal gratification in preference to the long-standing general

good. This is the message which Valmiki is trying to convey here through

Sumantra whom he describes as Mantra Kovida (an expert in the efficacy

of human voice).

The

Indian Constitution has added a new dimension to the concept of culture by incorporating a modern phrase ‘composite culture’

(Article 351) to promote the basic unity and integrity of the sovereign

democratic republic of India. In the Ramayana of Valmiki, we find a

comprehensive coverage to this concept developed on a far higher and almost a

global perspective.

Starting

with the national and human culture of public administration nurtured by the

devoted and dedicated ruler Dasaratha, the poet takes us though an infinite

variety of cultures including sage-culture, Vedic culture, work culture, family-culture, royal culture, rural

culture, tribal culture, animal culture, bird culture, forest culture,

terrorist culture, consumption culture, submissive culture, water culture, wind

culture, space culture, thought culture, speech culture, action culture and so

on. If we start citing instances of these various cultures, the entire story

will be told. What is relevant to note and appreciate at this point is the

marvellous way in which all these cultures were woven into a fine fibre of

life by the composite personality of Rama.

Starting

from Ayodhya, his march upto Lanka covers different areas where these cultures manifested themselves for his fraternal

touch. He mingled with the representatives of these cultures and gave them a

human touch, making human culture more dignified than even the culture of the

gods and the godmen. The most touching example of his accommodative spirit in

respect of cultural diversity is his alliance with Vibhishana, his friendship

with Sugriva, his sympathy for Ravana coupled with a genuine admiration for his

extraordinary valour and invincible courage and conviction. He treats the

tribal leader Nishada (Guha) as a personal friend and embraces him. He

performs the funeral rites for Jatayu, though unable to do so for his own

father. He tolerates Kaikeyi and tells Bharata not to misunderstand her. He

cares more for the coronation of Vibhishana than for his own re-union with

Janaki, immediately after the battle was over. He makes his wife walk through

the lanes of Lanka. He refuses to enter any town like Kishkindha and Lanka

till he completes his full period of exile. He accepts the divine aircraft–the

Pushpaka – for the sole compelling need to return to Ayodhya before the due

date, lest his brother Bharata should end his life by surrendering his physical

body to the sacred fire. This is the type of culture that Valmiki breathes into

his characters, particularly the two main characters – Rama and Sita.

But immediately after reaching Ayodhya, he

sends it back to its rightful owner Kubera from whom his brother Ravana had

grabbed it without any regard for propriety in matter of property. This

surprises even Vibhishana who recollects the characteristic smile of Rama while

accepting the offer.

Goswami

Tulasi Das too presents the cultural aspect of the story from a purely devotional point of view. In fact devotion or Bhakti

is the highest form of culture as it purifies the heart of the devotee and

establishes his perfect identity with the deity. As the devotee advances in

his capacity to visualise divinity, potentially present in all individuals,

the cultural values automatically get absorbed in him. This is what Tulasi

calls nirbhara bhakti and what Gita depicts as ananya bhakti. Valmiki

chooses to term this ‘Pararna Preeti’ (the most refined form of love). In fact

devotion is a chemical product formed by a spontaneous synthesis of pure love

and unquestionable faith. We find this devotional culture predominant in hundreds

of works written on the theme of Ramayana in Sanskrit and other

vernaculars.

Valmiki

depicts Hanuman as an ideal devotee balancing his acts of devotion with

awareness, obedience and execution. Manas too does not lag behind; rather goes

a step forward to place the devotee sometimes at the doorstep and sometimes at

the centre of the sanctum sanctorum of the deity Himself. No wonder if the

servant excels his master in some respects. Tulasi gives an example of Rama

trying to cross the ocean with the help of a bridge while Hanuman just

takes-off by his own propulsion. Tulasi also places Hanuman (Kapeeswara) at par

with Valmiki (Kaveeswara). The common

characteristic in the two seems to be their mastery over communication. Goswami

must have meticulously observed how Valmiki, himself, an exemplary exponent of

the calculus of speech shaped his favourite character Hanuman as his

mouthpiece. Both are splendid specimens of word-culture.

Of

all the types of cultures depicted in Ramayana, word-culture is the most

subtle and also the most relevant one for the modern world. It is the word that

creates the world. So the seers and the saints who handled the theme of Ramayana

paid special attention to this aspect

of word-culture so as to imbue the readers of Ramayana with this culture

of using the most powerful instrument of speech for their own satisfaction and

for others’ delight.

When Hanuman meets Rama for the first time on the outskirts of Kishkindha on the banks of Lake Pampa, what impresses Rama most is his art of speaking. It appeared to Rama as if it was not Hanuman that was speaking but his heart. This is the language of the heart which Hanuman cultivated and which pleases Rama most. More than the content conveyed, the manner in which Maruti presents it adds dignity to the diction. Rama exclaims at Hanuman’s skill in speaking, and tells his brother Lakshmana, “Look, how marvellously he speaks! He has not spoken a single syllabic without significance, he has not wasted a single word, nor has he missed an appropriate word. He has not taken more time than his ideas needed. Every word that he spoke can never be forgotten. Such a voice promotes general good and remains forever in the minds and hearts of generations to come.”

In

the light of what Rama has said about Hanuman’s speech, one can easily see why

Goswami equates Hanuman with Valmiki. Again when Hanuman sees Janaki for the

first time in the Ashoka garden of Ravana, Hanuman exclaims, “To find Sita here is just like listening to a person

devoid of word culture – who tries to say something, but actually says

something else.”

The

emphasis on word-culture can be seen in almost all characters of Valmiki including minor characters like Shabari,

Swayamprabha and Trijata and also Kumbhakarna who sounds highly cultured in his

presentation of an intricate problem and its practical solution to his adamant

elder brother, Ravana. A careful study of Valmiki from this point of view is

bound to promote word-culture in the modem world which is facing a communication crisis not only at political levels but

also in social and intellectual fields.

Besides

Rama, Sita and Hanuman, there are some major characters whose life and attitude towards life have an ocean of message to

convey for the betterment of humanity. Most outstanding among them is Bharata

whom Valmiki calls Bhratri Vatsala (favourite brother of Rama). Brother

Lakshmana is also equally dear and near to Rama, but there is a difference

between the two. Valmiki makes out this subtle difference between the two

brothers by keeping one very close both physically and temperamentally, while

the other enjoys not only affection but also admiration of the eldest brother.

That is why Valmiki calls Lakshmana a Lakshmi Vardhana (one who promotes grace

and grandeur). Even the youngest one Shatrughna is not ignored. He is Nitya

Shatrughna (one who puts an end to the eternal enmity within and without).

Rama, the chosen man of Valmiki, is of course, Satya Paraakrama (one whose

strength lies in his truth). Thus the four attributes given to the four

brothers communicate the composite culture nurtured by their elevated

thinking, noble functioning and ennobling words.

In

simplicity, humility and magnanimity Bharata ranks highest, partly because of

the ordeal to which he was subjected by the

unexpected turn of events. The shocking news of Rama’s sudden exile

immediately following the proposed coronation first upsets the father, then

mother Kausalya, thereafter the entire Ayodhya and finally the innocent and

devoted brother Bharata. Bharata had to establish his innocence and dedication

to his noble brother before everyone. He had to convince Kausalya first, then

Vasishtha, later even a sage like Bharadwaja and ultimately the perplexed and perturbed

audience at Chitrakoota. The dialogue

between Rama and Bharata in Chitrakoota is a monumental discourse on human

values in which both the brothers fight for their right not to rule but to

reject their legitimate power. Both of them had a claim upon the kingdom in

their own, way, but neither of them wanted to exercise it; for it went against

all canons of human culture. Ultimately they found a solution to the problem in

the sandals of the pious feet of Rama.

The

scene dominated by the dialogue between the two strong advocates of eternal

truth and immediate justice is an excellent illustration of practical philosophy, less preached and more practised in

thought, word and action. There are very few instances when Rama of Valmiki

preaches. The sermon on the mount Chitrakoota is an exception. On seeing

Bharata approaching him, Rama, even from that distance, could discern a prince

for whom propriety had a priority over power, and who has come to plead for

that traditional propriety which should not be sacrificed even if it leads to

momentary injustice. The words used and the thoughts expressed by the two

brothers amidst the sages and citizens of Ayodhya and Chitrakoota articulate

the lasting message that Ramayana has for the human society. Here lies a

lesson which the modem world will be wise in taking from this great

epic-particularly at a time when consumption, hoarding, exploitation, aggression

etc., have crept into the society eroding our cultural and human values.

If

Rama stands for truth, Bharata stands for justice, Lakshmana for duty and

Shatrughna for humility. Besides these four brothers, we have other

exemplifying figures. There are Vali and Sugriva, dealt with by Rama in his own

characteristic way. The three mothers – Kausalya,

Sumitra and Kaikeyi – stand respectively for modesty, magnanimity and determination.

Other women-characters like Ahalya, Anasuya, Shabari, Tara, Mandodari and

Swayamprabha also have their own philosophy of life which can educate

the modem world if properly understood. Swayamprabha is a character miserably

neglected by most authors; but she is the

most mystic, magnificent yet modest character who helps Hanuman and his friends

searching for Sita in getting through a critical situation. She literally leads

them from utter darkness of a closed cave to the broad daylight illuminating

the inquisitive waves of the ocean which bridges the gulf between Rama, the

mission and Sita, the vision.

Even

a very ordinary woman named Trijata visualises the ultimate victory of Sita and

cautions her fellow watch-women against thinking ill of her as the future of

Lanka depended on her mercy.

Let us consider the metaphysical message that Ramayana has to convey to those who have the necessary background. The entire Ramayana consisting of 24,000 verses is, in a way, an enlarged expression of Gayatri with its 24 key syllables (Bijaksharas), each syllable permeating through a thousand verses.

The

last word that can be said about the message of Ramayana to the modem

world is its emphasis on ‘general good’ (Shubham) as distinguished from its

counter-concept of victory (Jayam) which

forms the main thrust of Mahabharata. Ramayana provides the body for

Indian culture while Mahabharata fortifies it with the ‘mind’ that is

basically Indian but effectively human. These two works produced by two

master-minds of the world have served as supplementary readers for the students

of literature and culture through the ages. The purport of such works refuses

to be measured by relative scales of time and space. They are for all time to

come and for all people in the world.

The message of Ramayana is perhaps more meaningful to the modern world than to the ancient or medieval world as the modernity that we are proud of has been concentrating more on material prosperity, consumption of earthly pleasures even at the cost of the protection and preservation of the earth itself (which is gradually turning into an agnigarbha from the good old stature of ratnagarbha) and projection of self at the expense of fellow-beings. Valmiki uses a very beautiful word “madhavi” to convey the magnanimity and potentiality of the Mother Earth who produced a darling daughter, Janaki, who was dearer to the world than to the earth. She found her compeer in Rama, a jewel among the great rulers of solar race. The union of Rama and Sita is therefore an everlasting one – of heaven and earth, light and soil, truth and beauty, mission and vision, and above all of the Man, the embodiment of Dharma, and the Woman, the Chastity personified. What we need today is not a mansion, but man with infinite virtues to promote happy living in a peaceful world. That is the only answer to all the problems threatening the very existence of the terrestrial stability and celestial serenity in the modem world. Man-making, non-killing, sacrifice, sanctity, simplicity, integrity in thought, word and deed, and a firm faith in human dignity are the assets that Ramayana has given us. It is our duty to preserve them so that we are preserved as a race.