THE CONCEPT OF

GREATNESS

IN THE RAMAYANA*

First

lecture:

IN

RELATION TO MAIN CHARACTERS

Dr.

R. S. MUGALI, M.A, D. Litt.

The

Ramayana has been a perennial source of inspiration and instruction to all

those in

It

is obvious that the first four Sargas of this epic

which are prefatory in character were composed by one or two other persons, who

were probably the disciples of Valmiki belonging to a later period. It is

presumed that the actual composition of Valmiki begins with the fifth Sarga,

though it strikes sudden, and unconventional as an

opening canto without any salutation or prayer to the divine as in the

Mahabharata. Though the query in the first Sarga of the Ramayana is seemingly

innocent and anticipatory, based on a full knowledge of the entire story, it is

significant as a proper introduction to the great qualities of Rama, who is the

main character of the story and who is intended to be held up as a model of

virtue, a paragon, along with some other

characters, who vie with each other in emulating him and play their roles in

different capacities or relations, caring more for their devotion to duty than

for profit or position in life.

The

above-mentioned query and the answer to it clearly indicate the poet’s concept

of greatness and of the qualities, which distinguish an ideal person, a person

of true character and culture beyond time and clime. The Ramayana is the

earliest epic in Indian literature, produced a few thousand years ago,

containing an old story of the hoary past, mostly built creatively on the basis

of some real history and yet its appeal is universal in more senses than one,

mainly because of the great characters, who adorn its gallery and who stand as beaconlights on the rough waters of the sea of life. In the

said query made to Narada by Valmiki, and the reply that follows, the reference

is to the qualities of a hero like Rama of that particular time and yet some of

these qualities typify an Ideal Person of all time. Valmiki starts by asking

who is at present a man of virtue and a man of strength or heroism?” ![]() but in the course of

this dialogue we get the picture of an ideal person, who is not merely a man in

the present, that is

but in the course of

this dialogue we get the picture of an ideal person, who is not merely a man in

the present, that is ![]() but beyond it,

belonging to all time–past, present and future. A true epic or a great work is characterised by both its temporal and universal character

and that is why it takes its honoured place among

world classics. A man of great character or an ideal person is he, who is

virtuous, heroic, pious, grateful, truthful and firm in resolution. He is

possessed of good conduct and he is intent on doing good to all creatures. He

can control himself and conquer anger and prejudice. He is intelligent,

discerning and moral. He is eloquent in speech. He is accessible to all good

men as an ocean is to all rivers. He is noble and cultured and looks upon all

as equals. On the whole, the concept of greatness as indicated in the very

first opening canto of the Ramayana is fairly comprehensive, combining strength

with goodness, truthfulness with firmness, gratitude with the spirit of service

to all and self-control with self-confidence. Now it remains to be seen how far

this concept is exemplified in the life and conduct of Rama and other important

characters of this epic.

but beyond it,

belonging to all time–past, present and future. A true epic or a great work is characterised by both its temporal and universal character

and that is why it takes its honoured place among

world classics. A man of great character or an ideal person is he, who is

virtuous, heroic, pious, grateful, truthful and firm in resolution. He is

possessed of good conduct and he is intent on doing good to all creatures. He

can control himself and conquer anger and prejudice. He is intelligent,

discerning and moral. He is eloquent in speech. He is accessible to all good

men as an ocean is to all rivers. He is noble and cultured and looks upon all

as equals. On the whole, the concept of greatness as indicated in the very

first opening canto of the Ramayana is fairly comprehensive, combining strength

with goodness, truthfulness with firmness, gratitude with the spirit of service

to all and self-control with self-confidence. Now it remains to be seen how far

this concept is exemplified in the life and conduct of Rama and other important

characters of this epic.

It

is not possible to make a detailed study of the character and conduct of these characters

within the brief scope of these two lectures on the subject. Besides, we have

already before us very detailed and penetrating character studies by some

scholars, particularly the lectures on the Ramayana, delivered by the late Rt.

Hon. V. S. Srinivasa Sastri under the auspices of the Madras Sanskrit Academy

and published some thirty years ago. I shall confine myself to highlighting

some of the crucial situations, which illustrate the poet’s concept of

greatness. In the course of my study I was struck by the use of the word ‘Mahatma’

with reference to Rama and some of the other characters in numerous contexts

which made me think that Valmiki was very fond of that term as a yardstick of

greatness. I intend to find out what exactly is the meaning

of the word according to him and whether it means the same thing in all

contexts. I shall keep in mind the characters of Rama, Sita and others

belonging to the Kshatriya category in my first lecture and in my second

lecture I shall allude to the characters like Hanuman and Sugriva,

Ravana and Vibhishana belonging respectively to the Vanara and Rakshasa categories.

The

first question with which we are confronted in dealing with the character of

Rama is whether he was a character at all with human virtues and human

limitations. Not only that he is looked upon as God incarnate in popular

tradition, he is explicitly described as God in human form by the poet himself

in the very story of the manner of his birth and in other contexts. It is not easy

to ignore all that as interpolation. All the same, the total impression

that he makes on our mind is that of a great human being, who stood the test of

time, went through sorrow and suffering and rose above it, never swerving from

his cherished ideals of truth and duty. Even if he was an Avatar, which

literally means coming down, he descended to the human level in order to show

to what height a human can go and ascend peaks of divine perfection in the

midst of human imperfection. In brief, he appeals to us as a godly

man rather than a manly god.

The great qualities of head and

heart, which Rama was endowed with, have been praised in the first four Sargas along with the epithet of ‘Dharmatma’

and ‘Mahatma’, presumably on the basis of Valmiki’s

assessment in his original work, beginning with the fifth Sarga. It is natural

because Rama was born in the family of Ikshwaku

kings, who were Mahatmas all ![]()

![]() and continued the

noble tradition, thus giving rise to the great story of Rama. In the next

stanza, it is said that this Ramayana is a work, in which Dharma, Artha and

and continued the

noble tradition, thus giving rise to the great story of Rama. In the next

stanza, it is said that this Ramayana is a work, in which Dharma, Artha and ![]()

![]() thus hinting that the greatness of that family

and of its

scion, Rama, lay in the integration of these three Purusharthas

in actual life. The concept of greatness in the Ramayana is, therefore, not one

of neglect of worldly life, consisting of Artha and Kama but of building and developing it on the firm

foundation of Dharma.

thus hinting that the greatness of that family

and of its

scion, Rama, lay in the integration of these three Purusharthas

in actual life. The concept of greatness in the Ramayana is, therefore, not one

of neglect of worldly life, consisting of Artha and Kama but of building and developing it on the firm

foundation of Dharma.

The

first crucial situation in which Rama’s greatness was

tested after proper initiation and training by Vishwamitra

was that of coronation, nullified by Kaikeyi’s

overweening ambition and insistence. This has been worked out with masterly art

in all its complex light and shade in the first 20 to 25 Sargas

of the Ayodhyakanda. What is most important in this

tragic turn of events is how Rama, the hero of the epic, faced it with calm and

courage and upheld the noble traditions of truthfulness and self-denial for

which the family was known. When his father Dasaratha

told him that he would be crowned as heir-apparent, that is Yuvaraja, his friends

rejoiced and conveyed the news to his mother, Kausalya. She was overjoyed and

gave many presents to them. But Rama himself bowed to his father and quietly

made for his residence without expressing any of his feelings, almost like a Sthitaprajna. Probably he had some premonition of what was

ultimately going to happen. Or it may be that even at that young age his mind

was mature enough to realise that one should control

one’s feelings of joy lest it result in extreme sorrow and depression on

account of a possible reverse, which is inherent in any situation, particularly

where other claims can be made.

Dasaratha sent for him

again and asked him to be ready for the ceremony, which would take place the

very next day, as he was having bad dreams and untoward events might occur in

case of delay. Even here, Rama took leave of him and went to his mother’s

residence to announce the news without any display of sentiment. She was

extremely happy and said “all your opponents are finished.” ![]() .

This cryptic sentence is so meaningful not only because it

suggests that she was aware of his opponents but also because it hints at the

tragic irony of the situation. As it happened later, his opponents had not been

finished, her joy was short-lived and her misery was doubled by the reverse.

Rama asked Lakshmana, standing near him, to rule over

the earth along with him as he was like another soul of his and went home.

.

This cryptic sentence is so meaningful not only because it

suggests that she was aware of his opponents but also because it hints at the

tragic irony of the situation. As it happened later, his opponents had not been

finished, her joy was short-lived and her misery was doubled by the reverse.

Rama asked Lakshmana, standing near him, to rule over

the earth along with him as he was like another soul of his and went home.

The elaborate preparations for the

coronation, the enthusiasm of the people, Manthara’s

successful strategy of poisoning the mind of Kaikeyi,

Kaikeyi’s stubborn insistence on the coronation of

her son, Bharata, and sending Rama to exile, despite

desperate appeal by Dasaratha–all these are too

well-known to bear repetition. We have only to note here how Rama reacted to it

in a very graceful and dignified manner without expressing any sorrow. ![]()

![]() .

He positively told her that he would go to the forest as

desired and asked her to send for Bharata as quickly

as possible. In the course of his conversation with her, he told her with an

unperturbed mind that he was not hankering after money or power and that he

cared only for practising Dharma, which consisted in

serving his father and keeping the promise given by him. It may appear too

stoic and unnatural for Rama to react in this cool and collected manner.

Lakshmana in fact expressed his violent indignation

about it. But the poet wanted to show the greatness of Rama as an Ideal Person,

who valued moral and spiritual values as higher than worldly riches, power and

position. Rama is depicted as a Mahatma who was equal in joy and sorrow. He did

not rejoice when the glad news was conveyed to him nor did he feel depressed

when the news of the shocking reverse was communicated to him.

.

He positively told her that he would go to the forest as

desired and asked her to send for Bharata as quickly

as possible. In the course of his conversation with her, he told her with an

unperturbed mind that he was not hankering after money or power and that he

cared only for practising Dharma, which consisted in

serving his father and keeping the promise given by him. It may appear too

stoic and unnatural for Rama to react in this cool and collected manner.

Lakshmana in fact expressed his violent indignation

about it. But the poet wanted to show the greatness of Rama as an Ideal Person,

who valued moral and spiritual values as higher than worldly riches, power and

position. Rama is depicted as a Mahatma who was equal in joy and sorrow. He did

not rejoice when the glad news was conveyed to him nor did he feel depressed

when the news of the shocking reverse was communicated to him.

In the series of happenings that

took place consequent on Rama’s

resolve to go to the forest like the lamentation of his parents and the people,

the determination of Sita and Lakshmana to accompany

him, his speech and conduct were exemplary, befitting a great hero of noble

stature. The poet often refers to him as a Mahatma quite deservedly. But

this Mahatma had his moments of agitation and agony too. Sleeping on bare

ground on the first night after sending away Sumantra,

the charioteer, Rama said to Lakshmana in an agitated

state of mind “My father must surely be restless in sleep now. Kaikeyi must have been pleased that her wish is fulfilled.

Considering this suffering caused to us and the derangement

that has overtaken my father, I think ![]()

![]() .

Here is a strange irony of circumstance, in which a great hero, upheld Dharma

as superior to everything else, was impelled to regard

.

Here is a strange irony of circumstance, in which a great hero, upheld Dharma

as superior to everything else, was impelled to regard

![]()

![]() .

But

this was but a momentary outburst for he composed himself and appeared like

fire without a flame and sea without the surging wave. We find that in the

latter part of Ayodhyakanda commencing with the death

of Dasaratha, the return of Bharata

to the capital, condemnation of his mother’s act and his journey to the forest

to persuade Rama to come back and rule, Rama maintains dignity of demeanour in his refusal to return without fulfilling his

promise. He tells Bharata that neither he nor his

mother Kaikeyi is to blame

.

But

this was but a momentary outburst for he composed himself and appeared like

fire without a flame and sea without the surging wave. We find that in the

latter part of Ayodhyakanda commencing with the death

of Dasaratha, the return of Bharata

to the capital, condemnation of his mother’s act and his journey to the forest

to persuade Rama to come back and rule, Rama maintains dignity of demeanour in his refusal to return without fulfilling his

promise. He tells Bharata that neither he nor his

mother Kaikeyi is to blame

![]()

![]() .

This may be contrasted with his earlier rebuke of Kaikeyi.

.

This may be contrasted with his earlier rebuke of Kaikeyi.

The

next situation, which put the trio of Rama, Sita and Lakshmana

to a severe test, was that of kidnapping of Sita by Ravana, affirming the

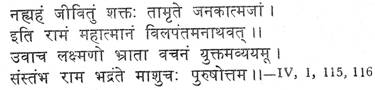

supremacy of ![]() in Kishkindhakand. Lakshmana had to console him when Rama wished to end his

life, though a Mahatma:

in Kishkindhakand. Lakshmana had to console him when Rama wished to end his

life, though a Mahatma:

The

sorrow of Rama welled up again when Hanuman returned from Lanka after meeting

Sita and gave to Rama the memento of Chudamani, sent

by her. He pressed it to his bosom and wept bitterly, tears gushing from his

eyes. He wanted to know all about her and said, “What is more agonising than this that I see the gem without seeing my

beloved, who wore it? You say that she can sustain herself only for a month in

my separation. But I cannot live without her even for a moment”, (V, 66, 9, 10).

Even when preparations for war with Ravana are going on, Rama pines for Sita’s company in an

uninhibited manner. Strangely enough, he is more open in expressing to his

brother Lakshmana the pangs of his separation from

Sita and his longing for her physical contact. He says to him with an air of

selfishness, “I am not sorry that my sweetheart is away from me or that she was

carried away by the demon. I am only sorry that her youth is passing away! My

body burns day and night in the fire of sexual passion.” (VI, 5, 5, 8)

One can see how perfectly human Rama was in such situations, in spite of his

being a high-souled person, or Mahatma. In the course

of the war, when a faked Sita’s dead body was shown

to him, Rama lamented awfully and fell down fainted. (VI 83, 10) Lakshmana had to console him, asking him not to behave like

a commoner, being a Mahatma. The strangest part of the whole story is that on

the death of Ravana in a prolonged battle, Rama accosted Sita, who came to meet

him, with mixed feelings of joy, pity and anger. He told her “You are standing

before me with your suspected character and causing pain to me like a lamp

facing a person with eye-sore. You can, therefore, go where you like. I have

nothing to do with you.” (VI, 118, 17-18) Sita had to proclaim her chastity

with a lump in her throat and tears in her eyes. In order to prove it, she fell

into fire and came out unscathed. It was only then that Rama accepted her as

his devoted wife, being reminded by gods that he was not an ordinary human

being but the Supreme God. Thus the image of Rama as a great character with

human weaknesses is conveyed to us, though it is not entirely self-consistent.

The

character next in importance is that of Sita, who has been called “Mahabhaga” on more than one occasion just as Rama is

called “Mahatma.” Her father Janaka, while offering

her in marriage to Rama, describes her as a devoted and large-minded wife, who

will always follow him like a shadow. ![]()

![]() .

This description was fully justified when she refused to stay back and

accompanied Rama to the forest, braving all the rigours

and dangers of a rough life. The four or five Sargas

of Ayodhyakanda, in which Rama vainly tried to

dissuade Sita from following him to the woods and Sita persisted on

accompanying him are some of the most noble and edifying portions of the

Ramayana. In this context, Sita argues powerfully in the highest traditional

manner how she must follow him, saying that all the defects pointed out by him

will be turned into merits by his love for her. (II, 29, 2) This has been

beautifully amplified later. (II, 30) But this very Sita, attracted by the

delusive golden deer, fell into the trap set by Ravana and became herself

responsible for all the misery that overtook her. In this tragic episode, it is

most unfortunate that she took Lakshmana to task in

the manner, most unbecoming of her when he hesitated to leave her alone in the

forest residence. She rebuked him with anger: “You are an enemy of your

brother, posing as a friend. It seems to be your desire

that your brother should die so that you can have me. You are not pursuing him,

because you covet me.” (III, 45, 5, 7) This may be explained as a very human

reaction in a trying situation. But the great Sita should not have attributed

motives in this abject manner, whatever her anger against him. Her intense

suffering during her kidnapping and captivity in Ashokavana

which enhance her steadfast loyalty to Rama evoke our admiration for

her. It is, however, a pity that Rama should have suspected her character and

ill-treated her at the time of their reunion. On the whole, the character of

Sita has been depicted as an ideal wife though she had her failings when she

was caught in a difficult situation.

.

This description was fully justified when she refused to stay back and

accompanied Rama to the forest, braving all the rigours

and dangers of a rough life. The four or five Sargas

of Ayodhyakanda, in which Rama vainly tried to

dissuade Sita from following him to the woods and Sita persisted on

accompanying him are some of the most noble and edifying portions of the

Ramayana. In this context, Sita argues powerfully in the highest traditional

manner how she must follow him, saying that all the defects pointed out by him

will be turned into merits by his love for her. (II, 29, 2) This has been

beautifully amplified later. (II, 30) But this very Sita, attracted by the

delusive golden deer, fell into the trap set by Ravana and became herself

responsible for all the misery that overtook her. In this tragic episode, it is

most unfortunate that she took Lakshmana to task in

the manner, most unbecoming of her when he hesitated to leave her alone in the

forest residence. She rebuked him with anger: “You are an enemy of your

brother, posing as a friend. It seems to be your desire

that your brother should die so that you can have me. You are not pursuing him,

because you covet me.” (III, 45, 5, 7) This may be explained as a very human

reaction in a trying situation. But the great Sita should not have attributed

motives in this abject manner, whatever her anger against him. Her intense

suffering during her kidnapping and captivity in Ashokavana

which enhance her steadfast loyalty to Rama evoke our admiration for

her. It is, however, a pity that Rama should have suspected her character and

ill-treated her at the time of their reunion. On the whole, the character of

Sita has been depicted as an ideal wife though she had her failings when she

was caught in a difficult situation.

Among

the other characters, who are regarded as great, Lakshmana and Bharata require

special consideration. Rama praises Lakshmana a3 his

inseparable counterpart but he appears to us to be an irascible and violent

counterpart on certain occasions. One can understand his resentment at his

father’s submission to Kaikeyi’s demands but he goes

to the length of exclaiming furiously that he should be imprisoned and killed.

(II, 21-12, 19) The poet still calls him a “Mahatma”. (II, 21-20) Probably the

word “Mahatma” in this and similar contexts means a heroic and eminent

person like the word “Mahanubhava” in a

restricted sense. But his real greatness or magnanimity manifests in his

sincere desire to accompany Rama and render all manner of service to him,

though there was no such compulsion, although he avers in a fit of anger that

he would kill Bharata if he ill-treated their

mothers. (II. 31, 20,21) He flares up again on seeing Bharata coming with his army under the wrong impression

that he was coming to attack them and shouted that he would fight and kill him.

(II, 96) One may ask whether these outbursts, though caused by righteous

indignation, are consistent with his magnanimity. Bharata,

on the other hand, is fraternal devotion and humility incarnate. He also has

been called a “Mahatma” in the true sense of the term. (II, 73, 28) His refusal

to abide by his mother’s demand, proceeding to the forest to persuade Rama to

return and rule, his acceptance of authority as a delegate of Rama and finally

handing it over to him on his return–all these acts and utterances hold him up

as a model of wisdom par excellence, though of course his censure of his mother

Kaikeyi is rather harsh (II, 73, 74) and lacks

restraint, whatever the provocation……Rama, Sita, Lakshmana

and

Bharata–these are the four great characters that the

author of Ramayana has delineated with superb skill. It must, however, be

remembered that their greatness is set off against their weaknesses and that

they are not mere, airy embodiments of one virtue or the other. All of them

represent the virility and magnanimity of the Kshatriya tradition along with

their limitations and weaknesses. They are depicted as ideal as well as human

even at the risk of a certain degree of incoherence.

Second

Lecture:

IN

RELATION TO OTHER CHARACTERS

In this lecture, we shall deal with some of the characters, who were friendly or hostile to Rama and his kith and kin. They are found both among Vanaras and Rakshasas. Unlike the Kshatriyas, the Vanaras and Rakshasas are non-human and therefore appear to be unreal and imaginary. It is a question how far they can be treated as human characters if they are creatures of the poet’s imagination without any basis of reality. If the Ramayana story is based on some substratum of history, is the latter part, in which characters belonging to these categories play a notable role, mere myth or a mixture of myth and reality? It is possible to argue that they were neither monkeys nor demons actually but human beings, resembling them, like the Dravidians and other tribal people, who lived in the hoary past. But their speech and behaviour show a strange combination of human and non-human characteristics. Some of them are endowed with rare qualities of loyalty, service and sacrifice. Their speech and action on certain occasions elicit our admiration so much so that we are inclined to ignore their unrealistic presentation. Their refinement and culture are no less than that of human characters, who have been held up as ideal. For the present purpose, we shall treat them as characters belonging to different categories and yet rubbing shoulders with human beings and helping or hindering them in their task.

Sugriva was among the

first of Vanaras, whom Rama met in his search for

Sita. When he came across Rama and Lakshmana for the

first time, he took fright of them because he feared that they were sent by his

brother Vali to put him to rout. Being, however,

assured by Hanuman one of his followers that they could not do any harm to him, he became friends with Rama and reposed complete

confidence in him. Being a co-sufferer, he showed great sympathy for Rama and

promised him that he would try his level best to search for Sita with the help

of his followers and sought his help in his own predicament.

This

occasion for mutual help was caused by a common grievance, viz., the kidnapping

of Rama’s wife by Ravana and the capture of Sugriva’s wife by Vali, though

the nature of the conflict was different in each

case. As promised, Rama joined hands with Sugriva in

the prolonged battle with Vali and helped to kill

him. Sugriva was then crowned as the king and

reunited with his wife, Ruma. He did not pay

sufficient attention to the task of searching for Sita in his absorption in

royal revelry. This saddened Rama and enraged Lakshmana.

He, however, realised his responsibility more keenly

than before and sent his armies in all directions with a specific assignment to

his minister, Hanuman. It was Hanuman, who found Sita in the Ashokavana of Ravana’s capital

after a good deal of adventure. In the events that followed, including a war

between the Vanaras and Rakshasas,

Sugriva played a major part and brought victory to Rama.

We

notice that he has also been called a Mahatma in more than one context.

In the first Sarga of Kishkindhakanda, it is said

that he, being a Mahatma, was frightened by the sight of Rama and Lakshmana. (IV, 1, 130) How can a frightened person be a Mahatma

in the true sense of the term? It is clear that the word means here a great or

eminent hero rather than a high-souled person. Even

in other contexts in this Kanda (3-21, 12-28 and 36-12) the meaning seems to be

the same rather than the original or the accepted one. He calls his brother Vali also as Mahatma, saying that he honoured

and bowed to his brother when he returned after killing Mayavi.

(9, 23) Vali’s wife, Tara, also calls him a Mahatma

![]()

![]()

![]()

Both

these Vanara brothers were heroic and generally

well-meaning. Sugriva was extremely helpful to Rama

though his help was reciprocal. ValI behaved almost

like Ravana in his capture of Sugriva’s wife. By no

stretch of imagination either of them can be commented with the epithet

of “Mahatma”, though Sugriva is a little more worthy

than Vali in receiving that kind of approbation. But

it must be said that the author of the Ramayana has used this term very often

without always conveying the sense, which it originally has and which strikes a

common reader.

Hanuman is

depicted in the Ramayana as the most ideal character in the Vanara

category, possessing lovable qualities of learning and culture, loyalty and

devotion, service and prowess. He occupies pride of place in more than half of

the epic, beginning with Kishkindhakanda. The Sundarakanda is almost exclusively devoted to him. The part

he has played in cementing the bond of friendship between Rama and Sugriva, in discovering Sita and instilling hope in her

heart and that of Rama as a brave and clever messenger, in his wonderful

exploits, of which he alone was capable, leading to the victory of Rama in the

war with Ravana and the reunion of Rama and Sita. All his achievements are

actuated by altruistic motives as he has nothing to gain for himself except a sense

of satisfaction on having helped a great hero like Rama out of his distress and

brought about a reunion of the ideal man and wife. If any one, among the

helpers of Rama, deserves richly the title of a Mahatma, in the true

sense of the word, it is Hanuman, beyond any doubt. In fact, he has been called

so on more than one occasion. When he crossed over to Lanka by his miraculous

flight, he was described as “Mahatma”, (IV, 1-208) implying both his great

prowess and his great devotion to duty, perhaps the former more than the

latter. Rama praises him profusely in the very first Sarga of Yuddhakanda on his return from Lanka after meeting Sita and

completing his mission. A “Purushottama” according

to Rama is one who achieves success as a loyal servant in carrying out a

difficult task with faith and devotion. By implication, Hanuman was such a

servant par excellence. Rama regrets that he cannot do any act of joy in return

for his service. So, he says, “the only thing I have with me is embrace and I

shall give it to this Mahatma.” ![]()

![]()

![]() Thus he hugged him

with great joy

Thus he hugged him

with great joy

![]()

![]()

It

has been pointed out that Hanuman was not free from weaknesses and shortcomings

in spite of his being great in every respect.1 One

of his weaknesses was failure of memory at the proper time under the curse of

the Rishis, whom he troubled during their Yagas while yet a boy. Among the examples given to

substantiate this is the one, in which he forgot that Sugriva

had already given orders to him early enough to send search parties for Sita

and placed the blame on his shoulders when Lakshmana

came to Sugriva complaining with indignation that he

had neglected his duty to Rama in his orgy of enjoyment as a king. Actually,

however, it was Hanuman, who first reminded Sugriva

of his obligation to Rama (vide IV Sarga 29) when Sugriva

ordered his army chief Neela to do the needful (IV,

29, 28-30). But he did not care to see whether his orders were carried out and

Hanuman had to awaken his sense of duty once again. (IV, 32) Though as a

minister of Sugriva, Hanuman had to share a part of

the blame, it is not correct to say that Sugriva on

his own had ordered Hanuman early enough. Some other examples of his amnesia or

forgetfulness are noteworthy. Notwithstanding all this, all the encomiums

showered on him such as: “He was great nearly in every sense of the word. And

if we take the deeds performed by him and put them in a heap, I doubt whether

the heap that stands to the credit of any other character would come up to it

in mere bulk. He performed great deeds of valour of

physical strength which no other living creature of the time could have

performed. Wise, moderate in council, always ready to see things while yet they

are only coming, few can approach Hanuman in sheer greatness, in weight of

achievement” are quite justifiable. There are, of course, exaggerations in the

treatment of his character 2 but the concept of greatness has taken

a very concrete shape in Valmiki’s conception and

delineation of Hanuman as an absolutely selfless, sincere, loyal, devoted and

discreet helper, ready to face any hazard and achieve wonders for the sake of a

great and venerable hero in difficulty and distress.

The

Ramayana, which would have been a grand saga of Rama’s

promise-keeping and self-denying greatness of character as a result of Kaikeyi’s greed, goaded by Manthara,

developed into a vaster and more tragic epic, worthy of being called a “Kamayana” as a consequence of Ravana’s

“![]() (V,

6-13) There are contexts in which the appellation

“Mahatma” appears to have been applied to him in the sense of a really great

man. (V. 9-73, 52-29, 59-34)

(V,

6-13) There are contexts in which the appellation

“Mahatma” appears to have been applied to him in the sense of a really great

man. (V. 9-73, 52-29, 59-34)

There

are other contexts in which the epithet “Mahatma” appears to have been applied

to Ravana in the sense of a great or famous hero. (V, 10-12, 59-24, 69-17)

Considering that the term has been employed in describing other demons like Narantaka (V, 69-71), other Vanaras

also, (V, 43-1, 49-2) it may be safely assorted that it is used in the sense of

![]() though the derivative and prevalent meaning of

the word does not justify such an extension. One of the most ideal and adorable

characters among the demons is Vibhishana, the

brother of Ravana, like Hanuman among the Vanaras

and Bharata among the Kshatriyas. The

greatness of the Ramayana is very much enhanced by the poet’s creation of these

characters, who shine like the Dhruva star, always

showing the path and direction of real character and culture, unsullied by

selfish desire and ego.

though the derivative and prevalent meaning of

the word does not justify such an extension. One of the most ideal and adorable

characters among the demons is Vibhishana, the

brother of Ravana, like Hanuman among the Vanaras

and Bharata among the Kshatriyas. The

greatness of the Ramayana is very much enhanced by the poet’s creation of these

characters, who shine like the Dhruva star, always

showing the path and direction of real character and culture, unsullied by

selfish desire and ego.

It

is well nigh impossible to be comprehensive in our treatment of this subject in

the course of only two lectures, which are a modest attempt to understand the

concept of greatness in this great epic. It may be said in brief that the

concept consists in suggesting that greatness is not perfectness

and that greatness shines all the more because of weakness or imperfection. It

is this deep understanding and depiction that has made Ramayana a great epic, a

magnificent human document, whose appeal is universal. It is wrong to look upon

this epic as a mere symbolic story of character-moulds or models. It is

certainly a picture of great men and women, whose greatness, however, is humanised by their limitations, weaknesses and failings. As

has been well said, “That is a great man, who, going through the mill,

undergoing my experiences, suffering my sufferings, enjoying my joys, still

comes out top, overcoming all those handicaps and limitations, showing in his

fullest development the grandeur of human character, approaching the divinity

from which he came and I came and you came, too”. 4

(It

may be noted that the references in these lectures are from Srimad

Valmiki Ramayanam, edited by Sri N. Ranganatha Sarma in Kannada

script.)

* Lectures delivered

under the auspices of the

1

V. S. Srinivasa Sastry: “Lectures on the Ramayana”,

Pp. 253-268

2 Ibid,

p. 253

3

Ibid, pp. 306, 307.

4 Ibid,

p. 13.